Thanks for the introduction, and thanks to Nova UX for inviting me to speak tonight. Bless you all for coming out on a cold Wednesday night to hear about design ethics.

Presentation

Overcoming the crisis of ethical debt in the design industry.

November 05, 2018 · Presented at NOVA UX

Thanks for the introduction, and thanks to Nova UX for inviting me to speak tonight. Bless you all for coming out on a cold Wednesday night to hear about design ethics.

I'm a senior UX designer in Viget's Durham office where I work mostly on digital products, doing user research, IA, prototyping and the like.

We're like the Falls Church office, but a little weirder. Just kidding. Falls Church is weird too.

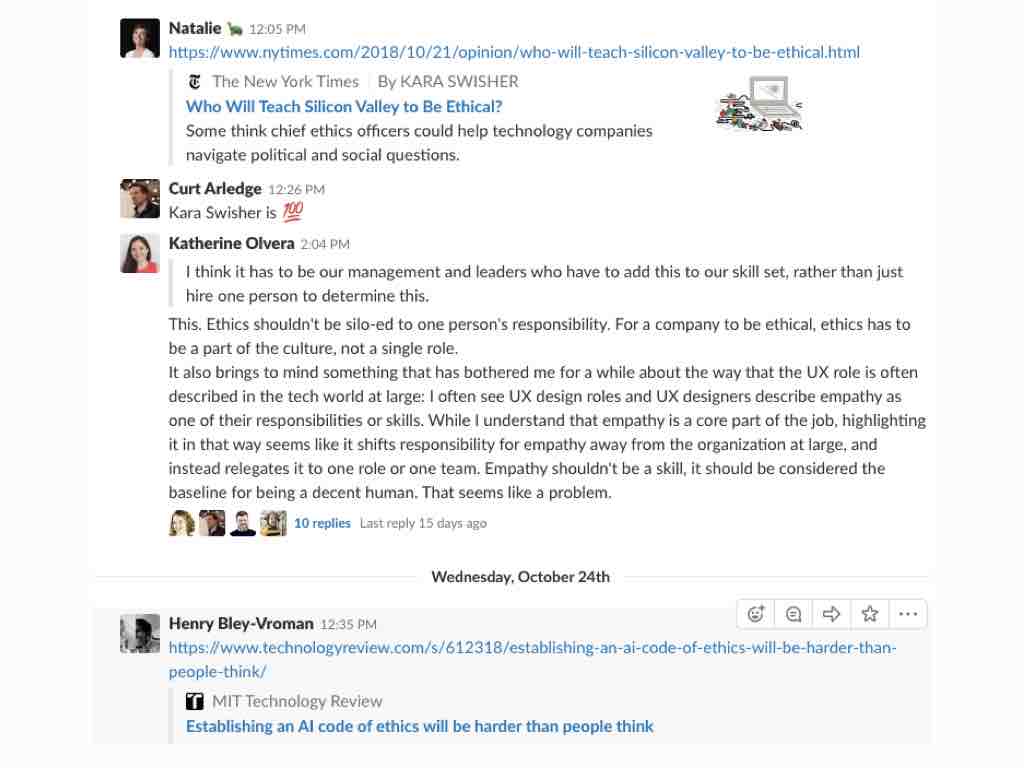

Before I start, I'd like to give a shout out to my coworker Curt for a lot of the thoughts I’ll share. He and I began discussing design ethics in earnest a few years ago, and probably spend more time than we should debating ethical issues with coworkers on Slack.

We have a channel devoted to the topic. It gets some healthy engagement. Lots of good content here.

We talk about a lot of things, like how the Web amplifies hate speech.

Or about China’s digital system of mass behavior control. People get “social credit scores” based on their behavior, buying history, friends, and web searches.

Or about how AI encodes and magnifies human prejudices. This is serious stuff.

We also talk about these things too. Chic felt blinders to keep you from getting distracted. People are raising money for these on a crowdfunding site near you.

By the way, have any of you seen this Portlandia skit? Uncanny. Distraction-cancelling glasses! What a world.

Design ethics is having a moment. This is partly a result of technology playing a larger and larger role in our lives. Ten years ago the iPhone was one year old. Today, we're checking our phones 150 times a day.

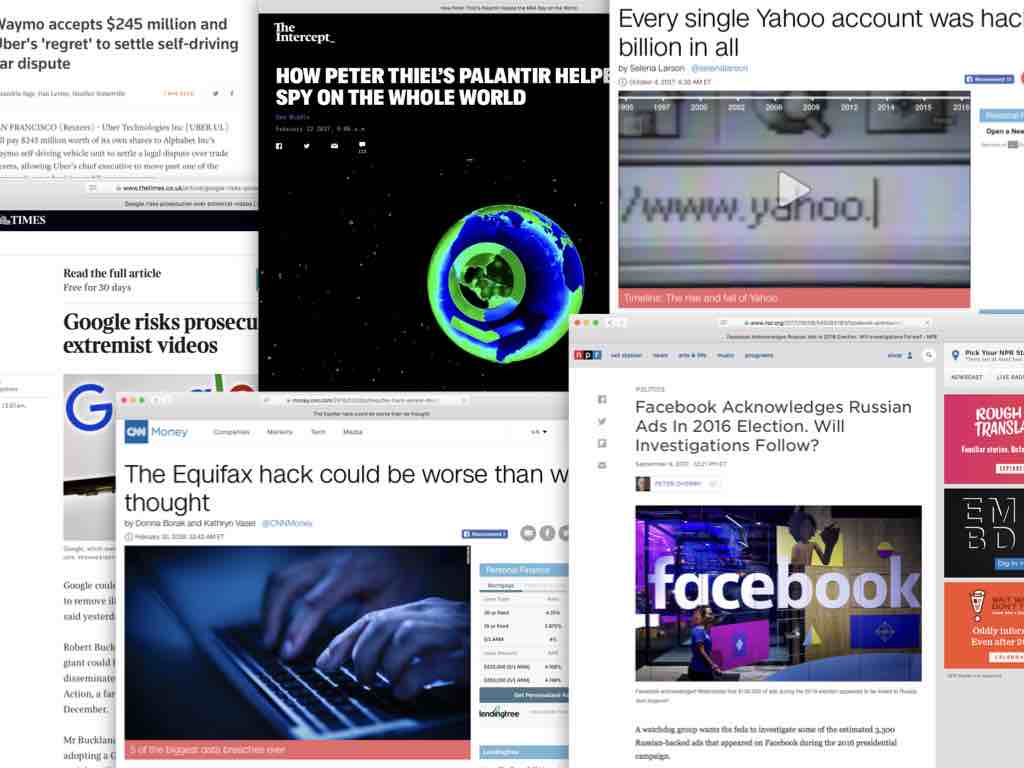

And there’ve been plenty of scandals at the highest levels of the Web. Big Tech’s negligence and abuses make headlines almost daily. Things like disinformation, massive data breaches, emotional manipulation — stuff that gets us into Black Mirror territory.

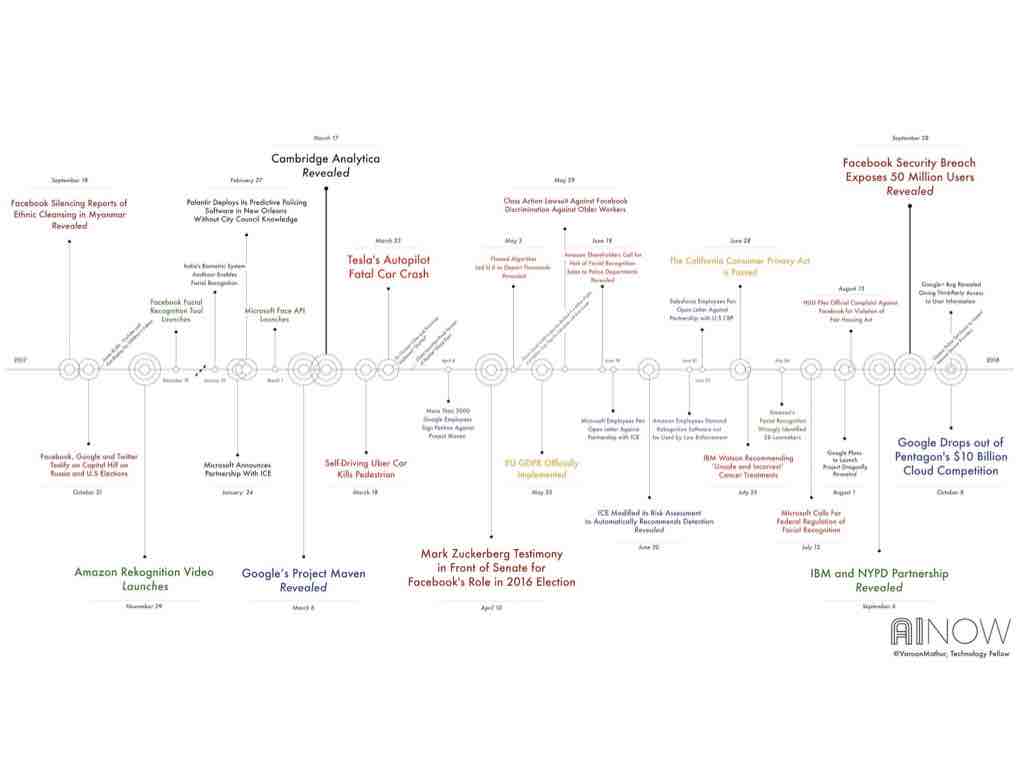

Here’s a timeline showing AI-related scandals just from 2017. That’s a lot of bad! I don’t work with AI, though, so it’s safe to assume I’m OK, right?

Also, this happened. Politics aside, the 2016 election changed public perception of our connected information technology.

The election of Donald Trump showed us, as a nation and in a very public way, that the health of our information ecosystem matters, that people can be nudged and manipulated at scale, and that our digital life has a real impact on the world beyond our screens. The stakes of our technology are getting increasingly higher.

We've started to question the ultimate benevolence of our digital technology and the people making it. This goes for the general public, but I think there is also a real identity crisis happening within our industry.

We're asking what role we, as designers, have played in loosing destructive technology on the world, and what we can do better. Or at least we should be asking these things.

Because the more I learn about the dangers of technology, I’ve come to wonder whether I’m somehow complicit in what’s wrong. Little old me, working at a tech company of 70 people.

I'm concerned about the future of the Web. We're seeing its potential for great good and great harm. But, frankly, at Viget we don’t often deal with these issues in our day-to-day work with clients.

We work with all kinds of clients, a lot of which are non-profits, higher-ed institutions, and medical clients. People trying to do good in the world. It’s one of the reasons I wanted to work there. We try to choose our clients well.

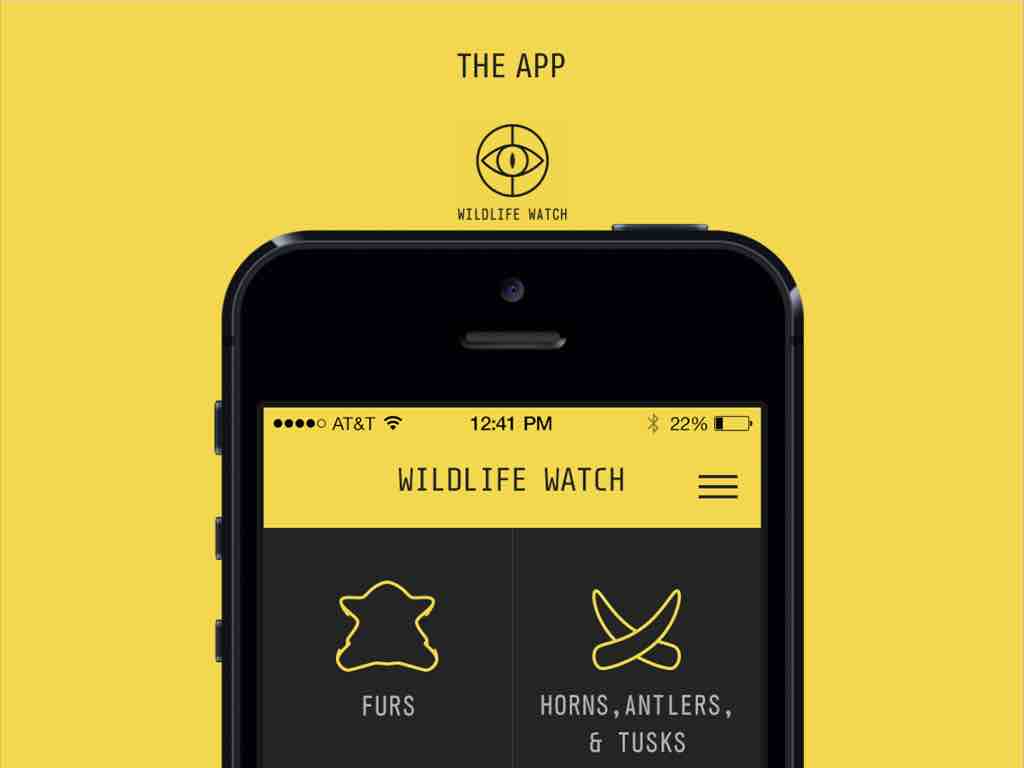

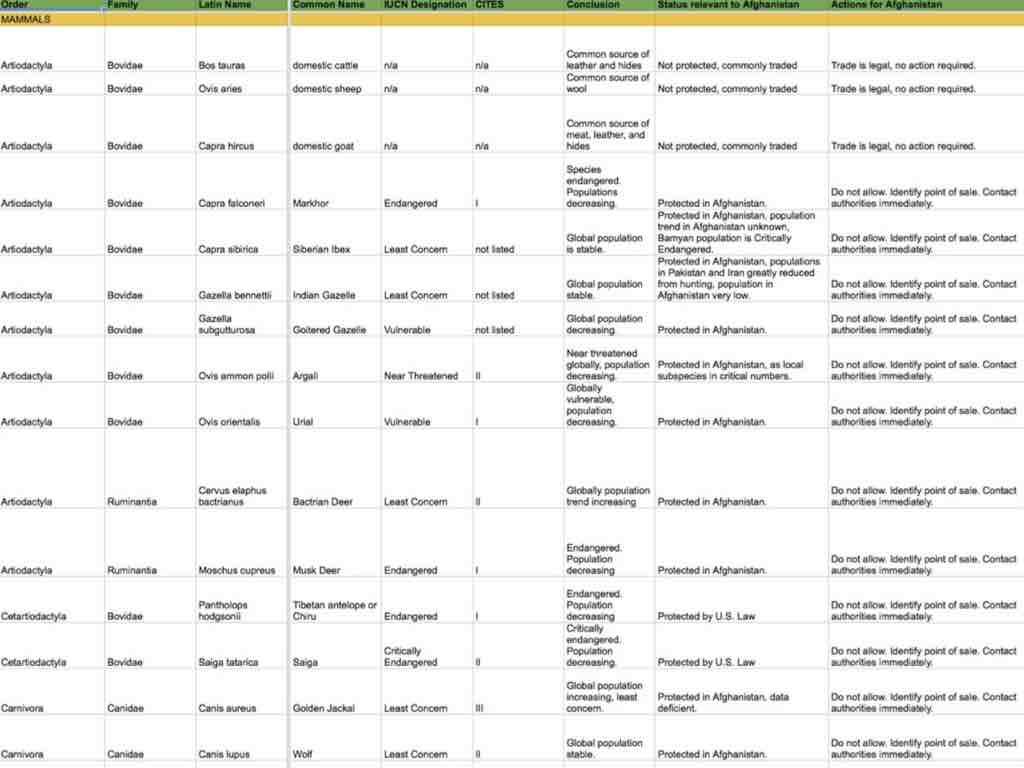

Because we make things like the Wildlife Watch for the Wildlife Conservation Society. It's an app that helps customs agents quickly identify animal pelts at customs borders. Not all animals are illegal to hunt, but it can be difficult to distinguish between them.

The UI asks simple questions about the item to help people understand what they’re looking at. The technology is benign, clearly using design for good.

One of our UXers made a database of all the logic needed to figure out what you’re looking at. This kind of stuff is the best.

It occurs to me a lot of us in tech don’t work in Big Tech, maybe most of us. We might work at a university, or a mid-sized product company, or a startup, or a smallish agency. Not all of us are on an inevitable march toward Silicon Valley. Unlike some, I don’t think it’s right to instinctively boycott working at these companies. They certainly need ethical-minded designers. Big Tech is broken, and needs to be fixed. But I want to make the case that change won’t come from the top.

So this is what I’m after: trying to understand the ethical dimensions of design in the day-to-day work that we do, for the rest of us who don’t work in Big Tech.

And something important to realize is that we really aren’t taught this stuff. Mostly we get by on instincts about right and wrong, following our conscience and intuitions, as we should. And that can get us far.

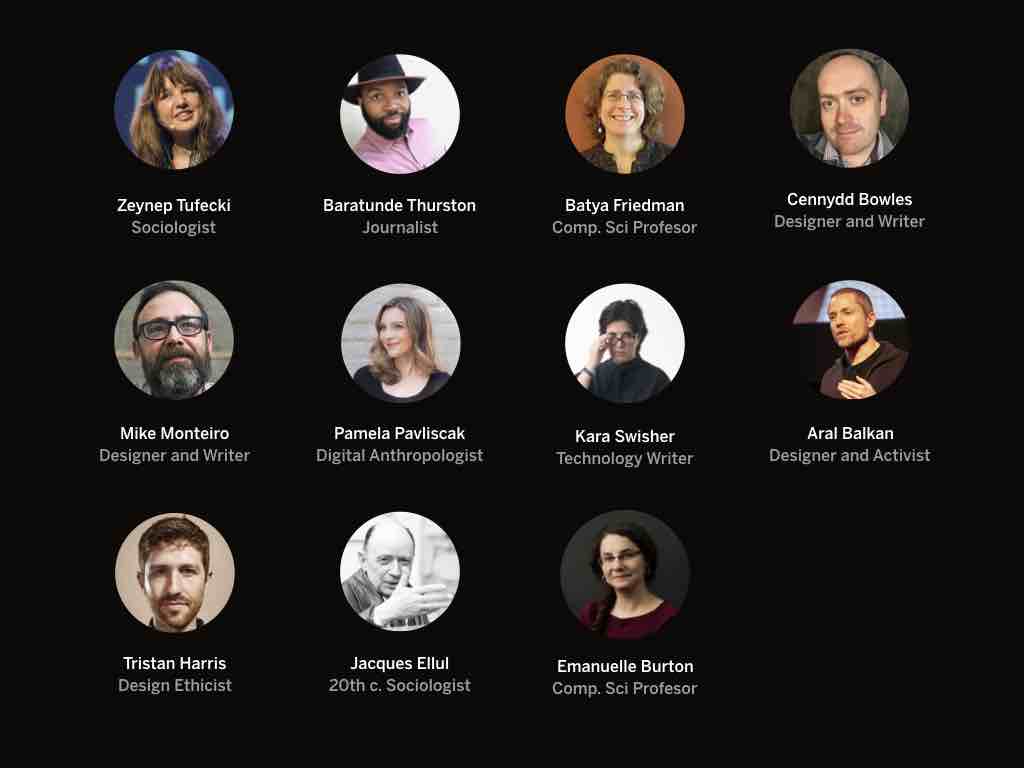

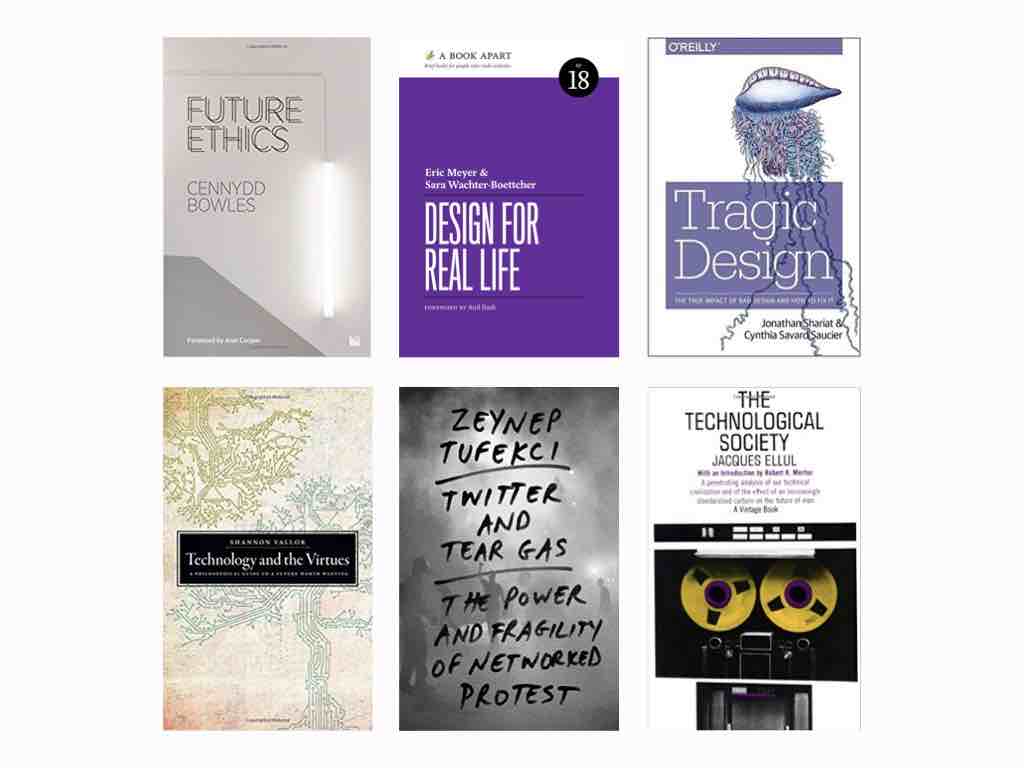

But there are some very smart people thinking deeply about ethics in tech who can help us strengthen our intuitions and learn to look deeper at the causes for the problems we face today. Here are some of them. I've heard Pamela and Mike speak a few times. I recommend looking these people up. I'll be referencing them throughout.

We need to self-educate, reading contemporary writing and old stuff, too. I’m not nearly as knowledgeable as I should be. I’m a designer talking about ethics, not an ethicist talking about design. But I’ll do my best to summarize for you what I’ve learned so far.

So let’s jump in. A good place to start is by asking what ethics is in the first place. I take ethics to be a way of thinking about the question, “What should I do?” Sometimes the answer to this is obvious, and most ethical misdemeanors don’t cross our mind, because most of us are nice people and design for others how we’d want to be designed for.

UXers tend to be conscientious people, after all. But are good manners enough? No one at Facebook set out to create a way to propagate hate. Well-intended people can create bad things.

Ethics isn’t just about being nice; it’s about interrogating our work. Holding it up against the things we value. Jacques Ellul, a 20th century sociologist of technology, puts it like this: “Ethics is not a matter of formulating principles but of knowing how to evaluate an action in particular circumstances.” Evaluating an action in context.

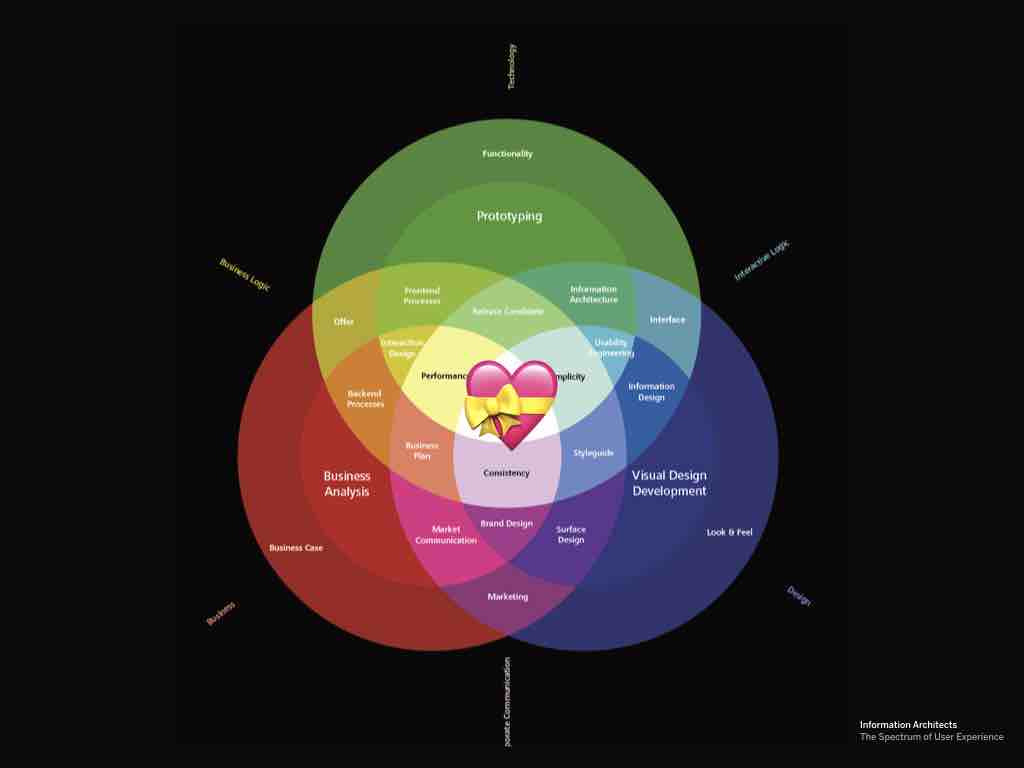

And if you think about it, this is the heart of UX: we think about design decisions in the context of lived human experience. UX has ethical concerns at its core. In a moment I’ll show that, although user-centered design has been misused by big tech, it still retains, at its core, potential for ethical renewal in our industry.

It can be tempting to want to codify design ethics to remove any ambiguity about right and wrong. To hold a conference and draft a manifesto and propagate it. And for the record, I think codes of design ethics should be used at all agencies, if only as a starting point for work with clients and for orienting new hires. “Here are the things we care about. Here are the lines we won’t cross.” I recommend reading Mike Monteiro's designer's code of ethics

We need guidelines and rules of thumb, but they’re only a starting point.

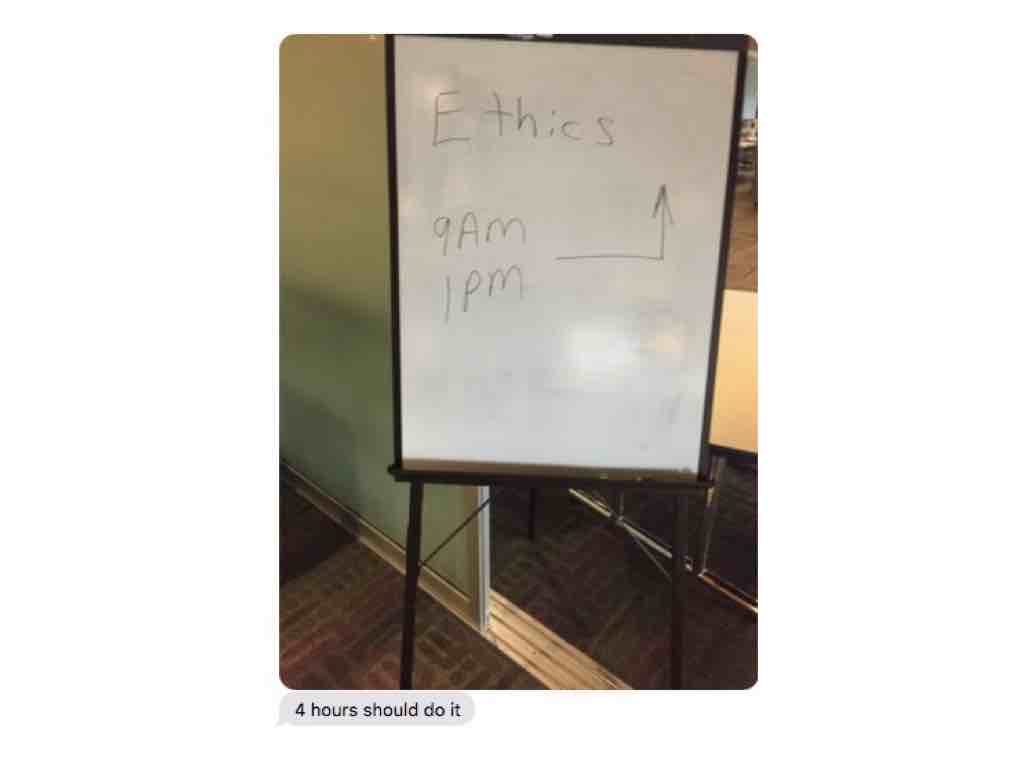

Because the thing is, oaths are easy to forget. Rules are easy to check off and be done with. Schedule an ethics meeting and move on. A friend of mine saw this at his office. Four hours should do it.

It looks like something Tim Ferriss might've come up with. The thing is, codes don’t change the way we think, and we need to learn to see differently.

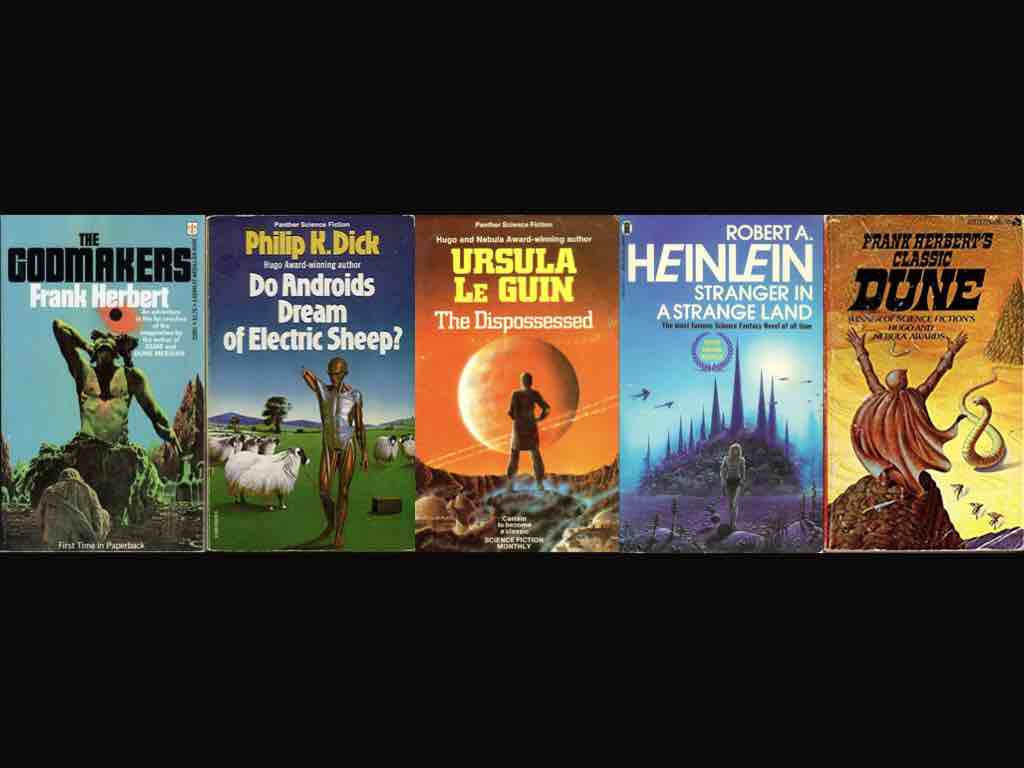

Some professors are using fiction, especially science fiction, to help students grapple with ethical situations. Fiction offers students some distance from the situation to think critically about it, and science fiction helps us to think through the consequences of technology that hasn’t been invented yet. Literature can help us see the world in human terms. Show of hands of folks who were English majors? (I was.)

Design ethics is an ongoing conversation, because as soon as we find solid ground, a technology is invented a month later. It's like agreeing on the safest way to cook with fire, and then a microwave shows up. That might be an extreme example.

As a society, we’ve been playing with fire for a long time. Remember Prometheus, the guy who gave humanity fire, and was punished for eternity by the crow that ate his liver every day? Fire is life-giving and deadly.

We need to realize that our innovations always outpace our ethics. It takes us a while to adjust, if we ever do. We’ve been wrestling with the consequences of our technology since a caveman first burnt his finger.

And this wrestling often ends in a stalemate. I'm going to go down a little rabbit hole here, but hang with me. It's worth it.

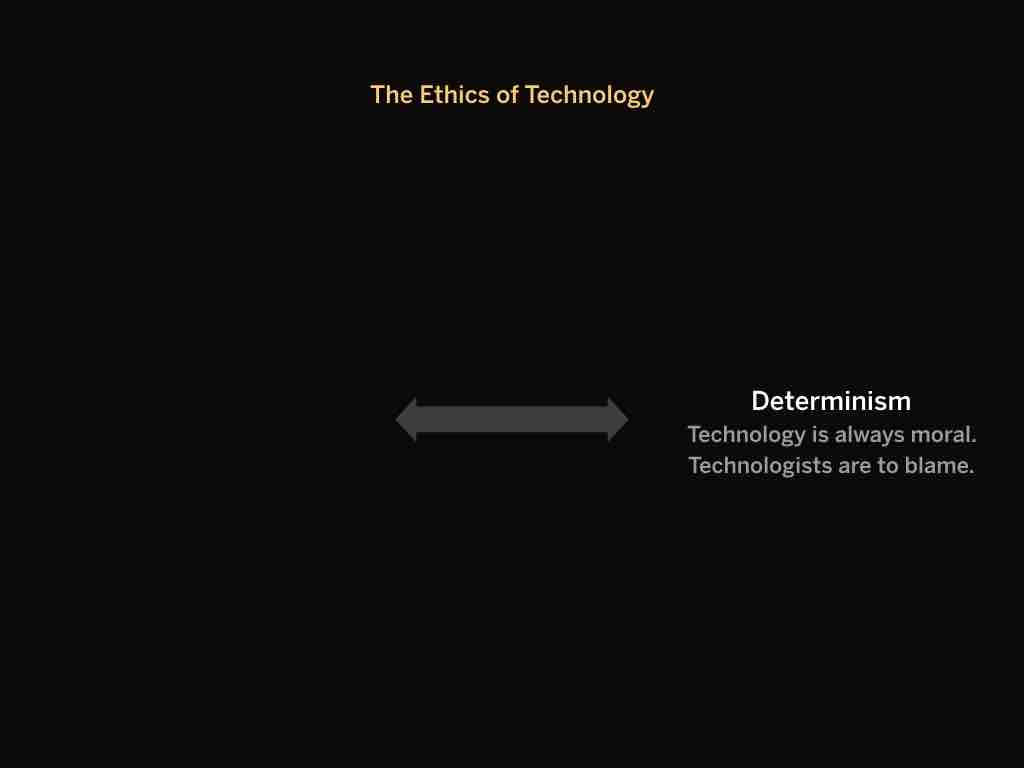

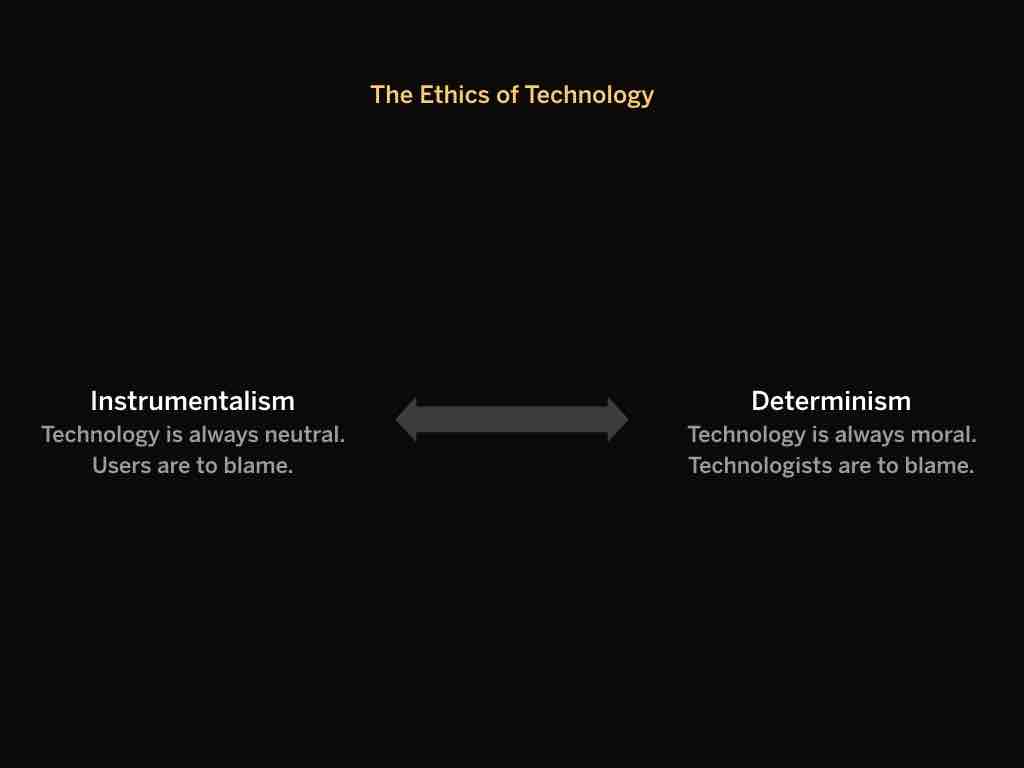

Generally speaking, there are two camps that people tend to fall into when it comes to the ethics of technology.

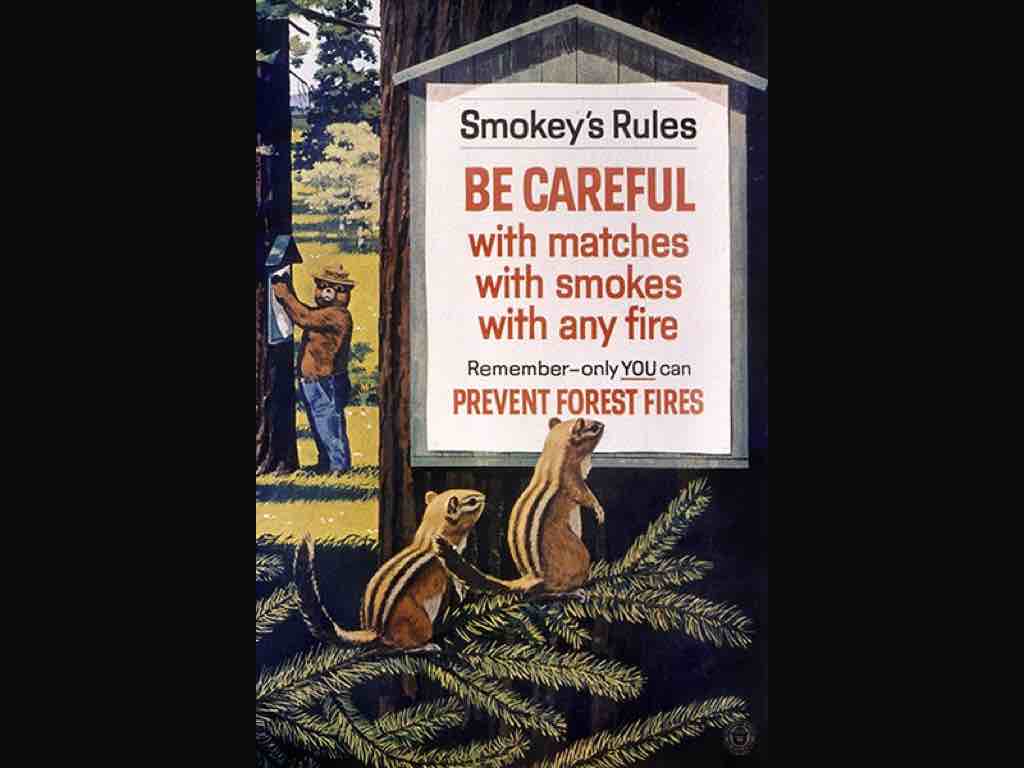

On the one side are those who say technology is morally neutral. A brick can be used to build or destroy. What matters is how someone uses it. The technical term for this viewpoint is instrumentalism. And we can see the merit of this: all of us can choose what to do with a brick.

The downside of this view, though, is that it allows technologists to shirk moral responsibility for their decisions. They can blame bad actors for the damage caused by use of their technology. This is the dominant point of view in Silicon Valley for obvious reasons.

On the other side of the spectrum are those who say design decisions are always moral decisions. The things we design shape the way we act. Bricks are designed for building, but weapons are designed for hurting people. So if you design something that tends to hurt people, whether or not you meant to, you are acting unethically. The technical term for this view is technological determinism.

Instrumentalism puts the ethical burden on users. Determinism puts the ethical burden on technologists.

This is a very reductive view of the problem, but it illustrates why commentators end up talking past each other. And they don’t account for ambiguous things in the digital age that do immense good while doing immense harm. Facebook was complicit in the spread of disinformation about the Rohingya tribe; it also has a Crisis Response hub that gives people in disaster areas critical information.

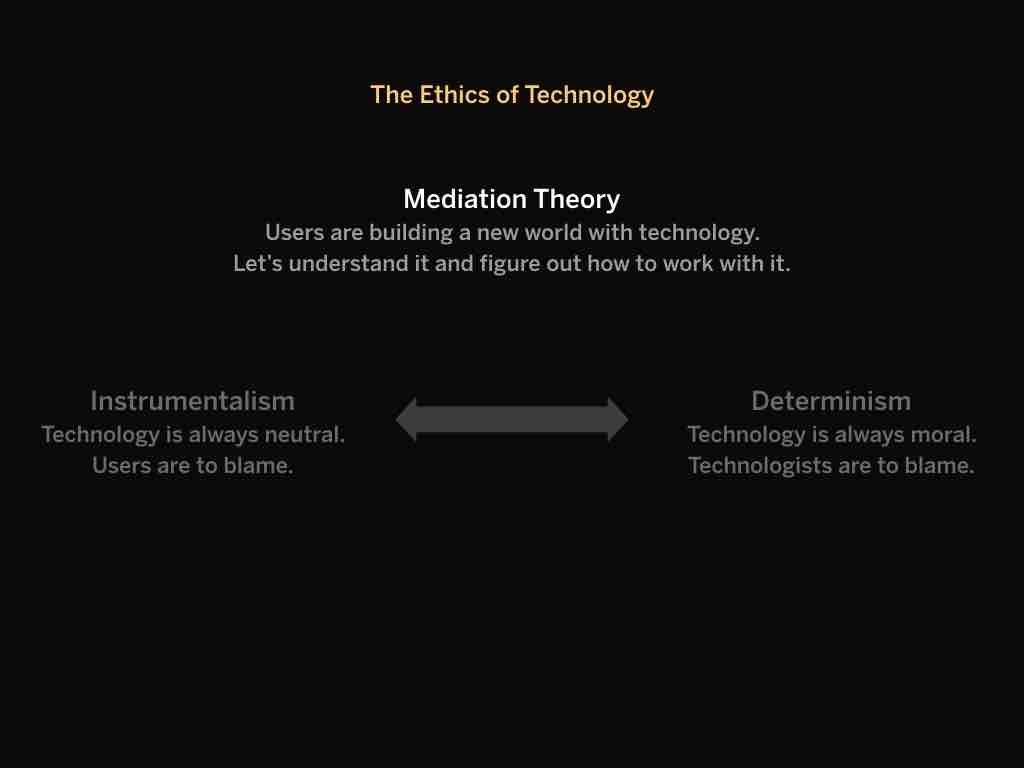

A third view has been developed recently that avoids the pitfalls of the instrumentalist and deterministic views. It’s called mediation theory, which argues that “we don’t fully control tech, nor does it fully control us; instead, humans and technologies co-create the world” (Cennydd Bowles, Future Ethics). We’re creating a world together. People are beginning to think about what it will mean for humans to coexist with AI, for example.

Mediation theory focuses on the interplay of technology and human interaction. Think of a violinist: is the music the result of the musician or instrument? The result can’t be located in either, but in how they interact. When we talk about design ethics, we’re talking about proper design and proper use. We’re also talking about how use influences design, and vice-versa.

But unfortunately, the music isn’t always good. Sometimes it’s pretty awful. And sometimes designers get blamed.

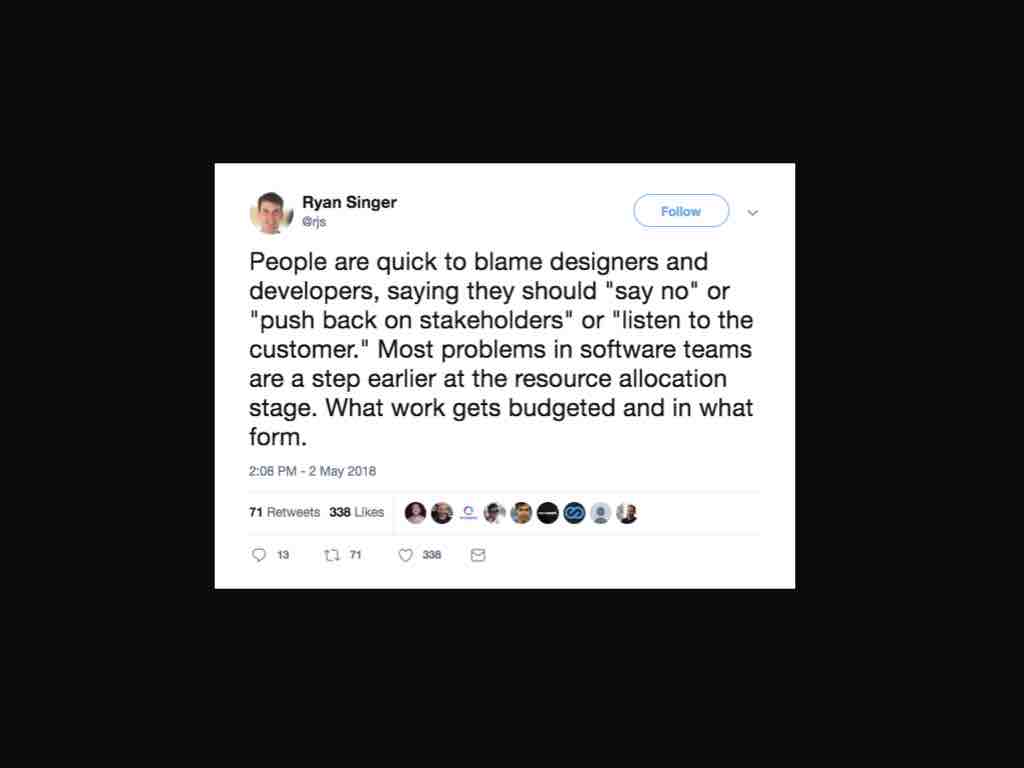

Designers are certainly complicit in the ills of the web. As Ryan Singer points out here, though, sometimes problem begin higher up the food chain.

Points like this got us thinking: What responsibility do designers have when it comes to tech ethics today? And what if problems that show up in design are consequences of deeper issues?

I’m going to walk through a model that explores those deeper roots, to try to show the context of our work as designers.

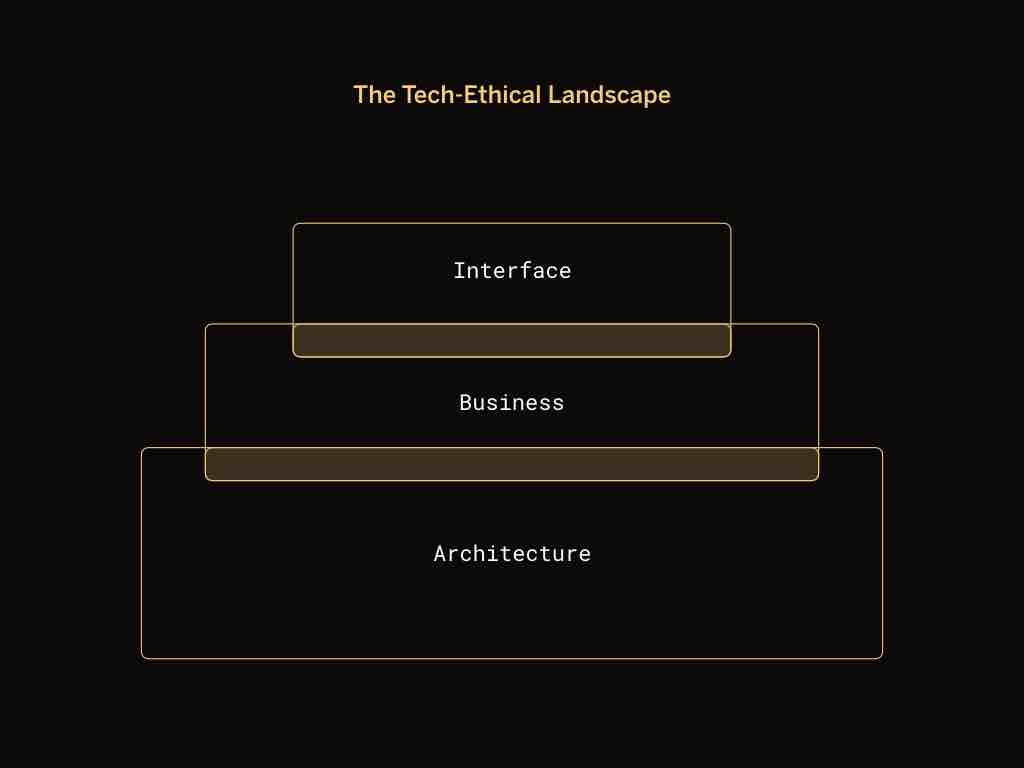

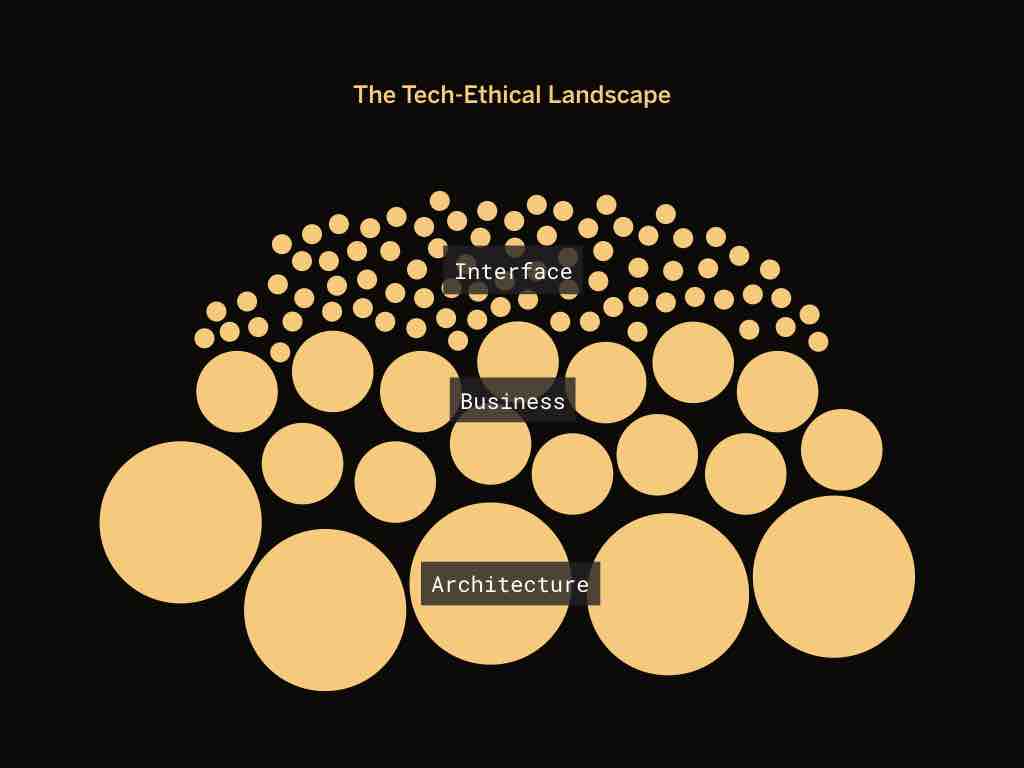

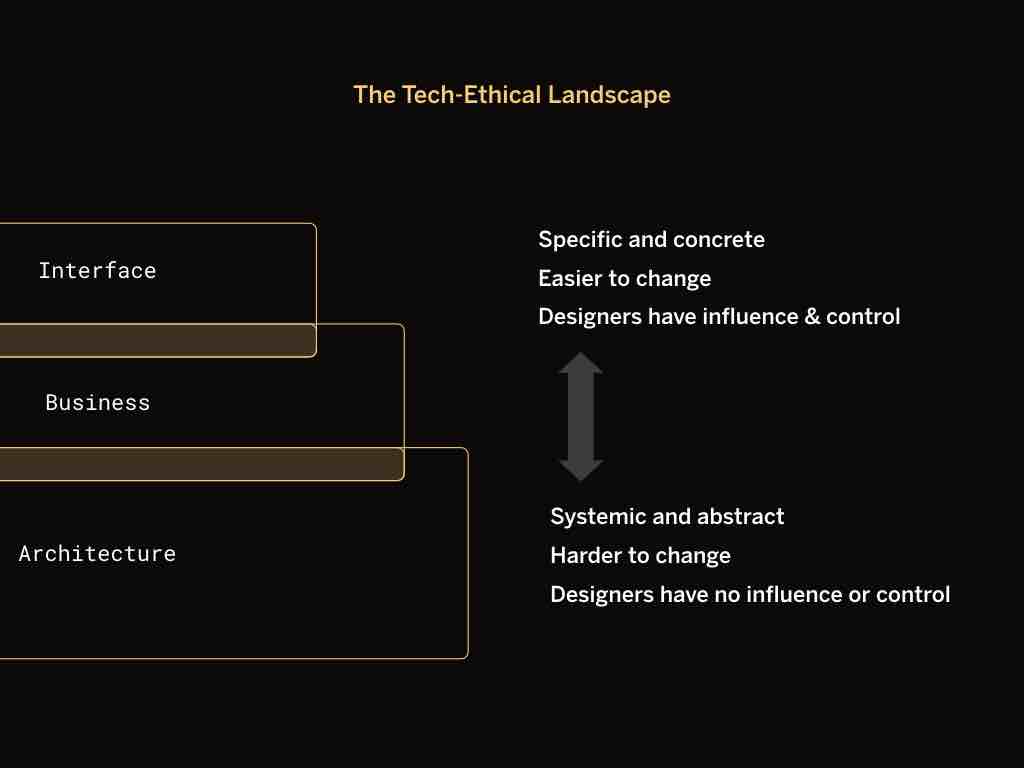

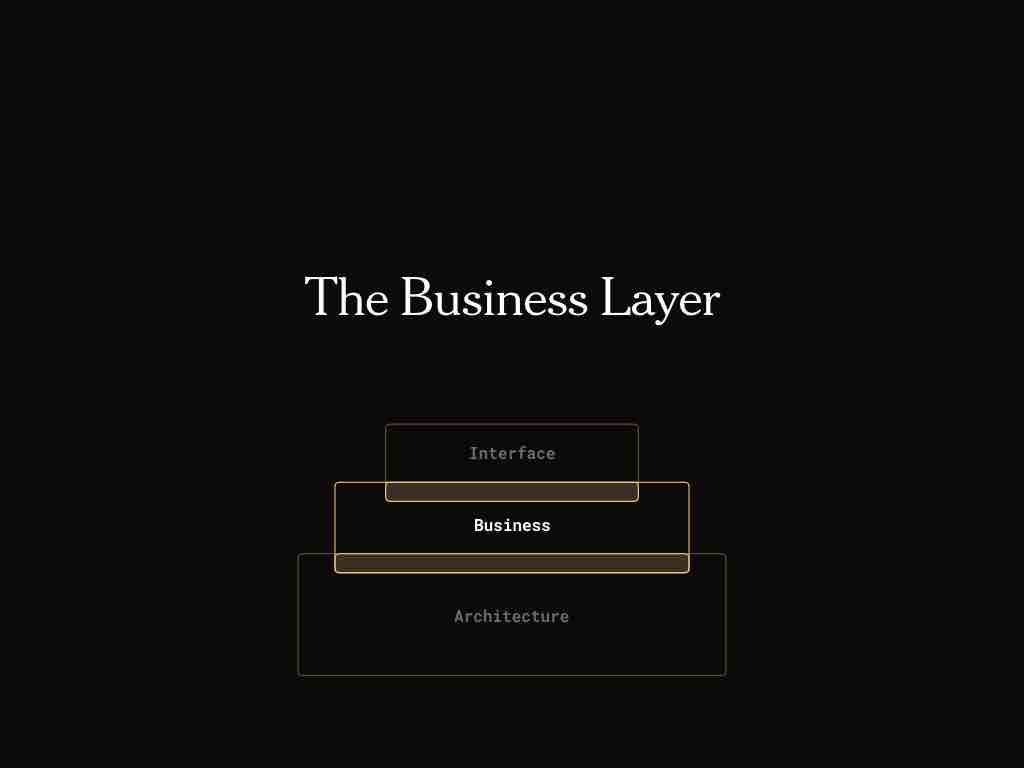

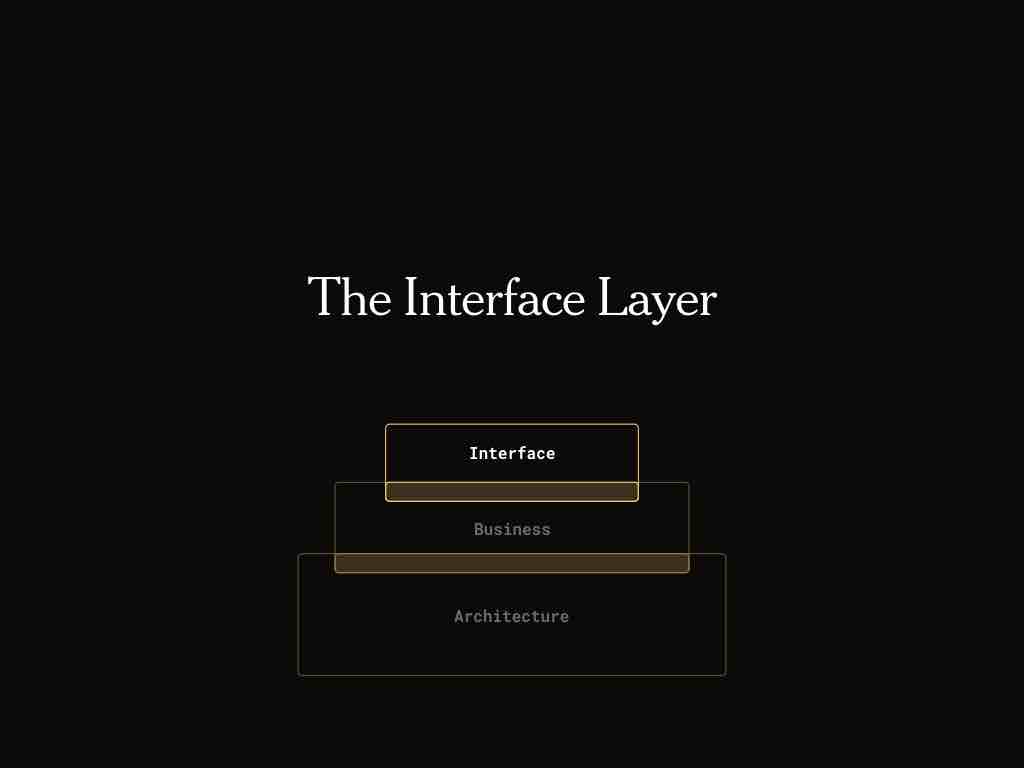

Broadly speaking, these are the layers that make up the web: architecture, business, and interaction. Each of these layers overlaps and builds on the next, and each has unique ethical concerns.

Another way to look at this model is as a sum total of design decisions made on the web. At the architectural level they are deep and pervasive, and generally speaking fewer decisions are made. At the business level they get a little more diverse. And then at the interface level, you have a proliferation of granular decisions, things that can be changed with a line of code.

At the top are things that are specific and easy to change, and designers are in full control; at the bottom things are systemic and diffuse, and designers have little to no control. For the sake of visual simplicity, I’ll stick with the stacked layers.

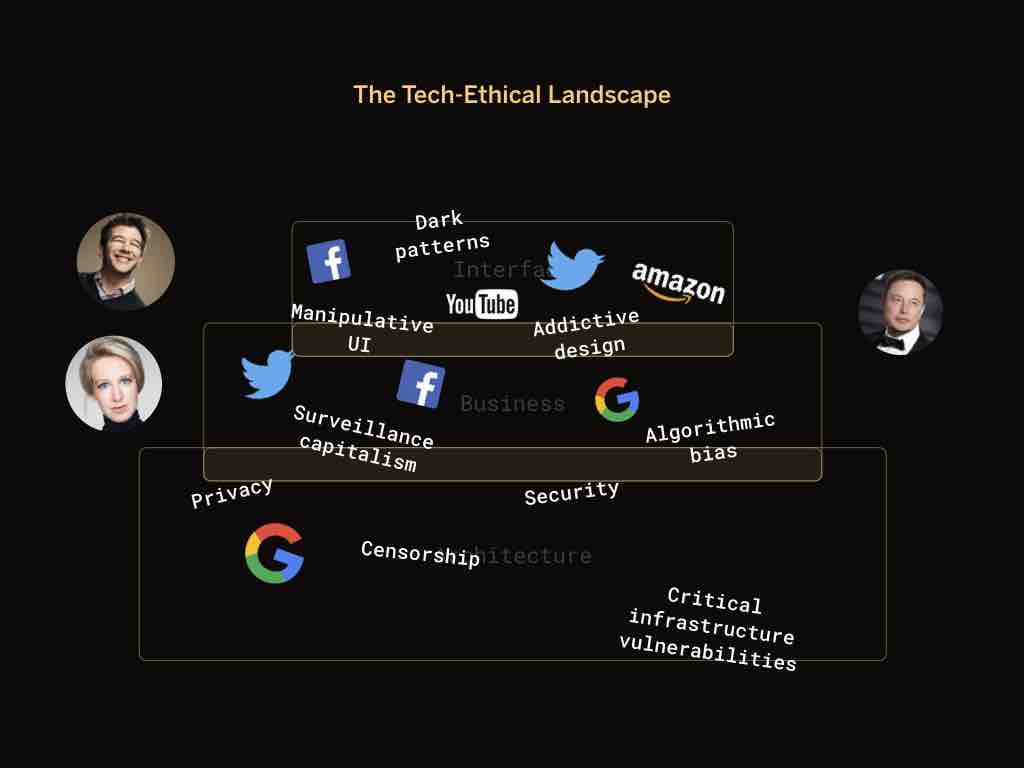

Here’s a little of what’s going on here. There are problems all over the place. We’ve got problems that have existed since the dawn of the Web. We have infrastructure vulnerabilities. We have businesses using Web technology in psychologically manipulative ways. We have designers using distracting UI to obscure important details. Elizabeth Holmes is deceiving investors about her technology. Elon Musk is tweeting stupid things. Whew.

When we talk about systemic bias or CEOs tweeting dumb things, these are what we might call failures of corporate and professional conduct. These clearly have ethical consequences, and can lead to design problems. And as employees at their companies, designers have a responsibility to confront these issues. But what we’re mostly talking about today are the ethical dimensions of digital products.

People and organizations with considerable influence are using their influence poorly, making our world more challenging to live in; so what do we with our limited influence? For one, we need to understand how ethical issues are interconnected. Many of the problems making headlines today are perennial problems with the core architecture of the Web. They’ve been with us from the start, though it’s taken thirty years and congressional hearings with Silicon Valley CEOs for conversation about tech ethics to go mainstream.

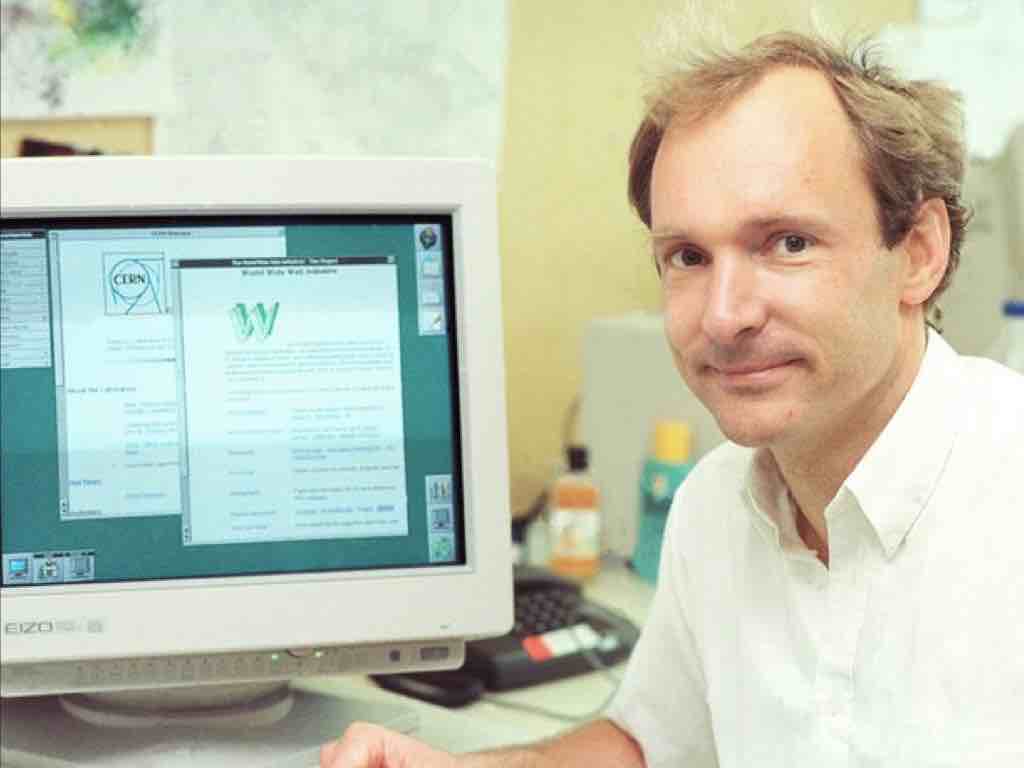

Tim Berners-Lee, the man who created Web technologies like the URL, hypertext, and HTTP, anticipated many of these issues early on. In his 1999 memoir about inventing the Web, he wrote that “Information quality, bias, endorsement, privacy, and trust — fundamental values in society, much misunderstood on the Web [make it] highly susceptible to exploitation by those who can find a way.”

And in an interview a few months ago, he gave an even more grim assessment: “The increasing centralization of the Web has ended up producing—with no deliberate action of the people who designed the platform—a large-scale emergent phenomenon which is anti-human.”

This is a powerful quote. For one, he acknowledges that no one intended for us to get where we are, with Google properties owning 90% of search traffic, and Amazon owning 50% of the ecommerce market. One of his core principles for the Web was that it remain decentralized, with no one organization controlling traffic. Yet we needed help finding information online, and so search engines began popping up, and eventually you get Google, which earns $30B a year selling user data to advertisers.

And he uses the word “anti-human” to describe the way his technology has been used to take advantage of people, emotionally, psychologically, and politically. We’re at a point where advertisers or politicians can use artificial intelligence to tailor messages in specific ways to people based on demographic information.

In particular, four key features of web architecture have led to many of the issues we see today. What began as ideals have been distorted and misused. I’ll walk through these briefly.

This first point seems so self-evident that it hardly needs to be said. The Web is an interactive medium, as opposed to a passive medium. We talk about “users” because the Web is used, not viewed.

Unlike television, film, or print, people on the Web can take direct actions on the Web while using it. They can say things, buy things, take and share things – not as a side effect of the Web but because of the Web. The endless possibilities for direct user action, and the way digital objects are designed to enable or discourage various actions, is a bedrock issue that shows up in every level of the ethical model.

The web’s interactivity and measurability makes it an ideal medium for behavior manipulation. This isn’t necessarily insidious. But what we don’t often realize is that the interactive nature of the Web creates a power imbalance between users and creators. Architects have known this for centuries.

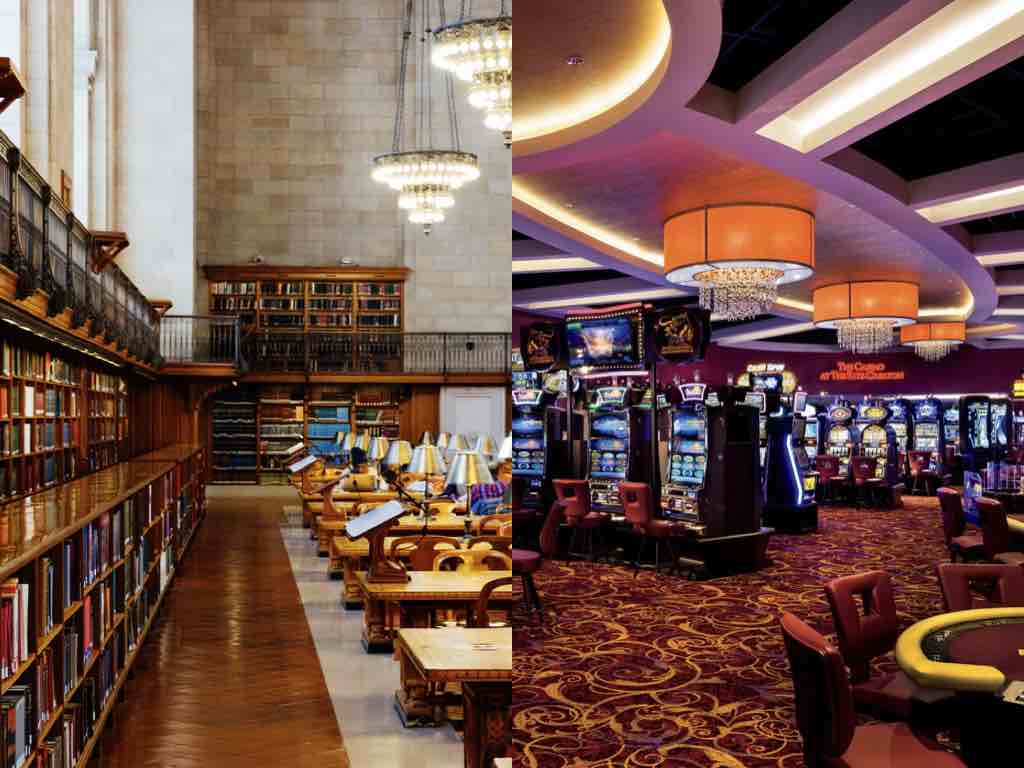

The designers, engineers, and business interests are world builders, controlling the environment, setting the rules, and playing to people’s natural human tendencies. We get to choose whether we are building a library or a casino for our users.

Also, the Web is open. Anybody can use it, and that creates a whole bunch of ethical considerations that have been around since the earliest days of the Web.

Even as he was developing his early ideas for the Web, Berners-Lee was aware of the social consequences that could arise from a network like this, seen in the quote I mentioned earlier. Some of the earliest Web critics emphasized the dumbing-down effects of a platform that elevates folk wisdom over expert knowledge. If you don’t like what an experts says, there is always another website or Youtube video with a second opinion.

Zeynep Tufecki, a sociologist at UNC, makes the point in a TED talk that

“Many of the most noble old ideas about free speech simply don’t compute in the age of social media. John Stuart Mill’s notion that a “marketplace of ideas” will elevate the truth is flatly belied by the virality of fake news. And the famous American saying that “the best cure for bad speech is more speech”... loses all its meaning when speech is at once mass but also nonpublic… How can you cure the effects of “bad” speech with more speech when you have no means to target the same audience that received the original message?”

She points out that it’s now possible to deploy persuasion architectures at scale in such subtle ways that we don’t have the opportunity to collectively resist them. It could be Zappos trying to sell us shoes or a politician spreading disinformation about his opponent. We don’t share the same experience with one another on the Web.

Another feature of the infrastructure is that it affords quantitative measurement. Because metrics like pageviews, time on site, and engagement are simply available to us, they naturally become a kind of default way of understanding user behavior. This data is easier to get than qualitative data about user experience, and it’s often regarded as more reliable and less vulnerable to bias, but this is demonstrably false.

And there is so much that data can’t tell us about the user experience. For example, a metric like pageviews is clearly not a proxy for the quality of the content or the user experience. “User engagement,” “time on site,” and “monthly active users” are rightly understood as vanity metrics.

Cennydd Bowles, a Welsh design ethicist, rightly argues that,

“At the heart of the dark pattern, the addictive app, and the disinformation problem lies an undue fixation on quantification and engagement.”

So as designers, we need to learn to critique the underlying ideas and aspirations that are causing irresponsible design. We need to show clients, coworkers, and higher-ups the practical consequences of their decisions.

And last, the web still technically is decentralized, but certainly not the way Berners-Lee intended.

Today, over half the world’s population is online, and over half of them are monthly active user on Facebook. Including its subsidiary YouTube, Google currently accounts for 90% of all search traffic, and estimates suggest that these two companies account for 75% of referrals to top publishers online. Both companies monetize this traffic through ads, and since 2012, Facebook has quintupled in total market capitalization and Google has quadrupled.

As digital designers, our professional domain is built on top of an infrastructure that is skewed to serve a few giant companies rather than the health of our society. And for designers, we are pretty much powerless to change it. The design of this infrastructure is a fundamentally political challenge and that we will only solve as citizens, not designers.

As Tufekci reminds us,

“In the 20th century, the US passed laws that outlawed lead in paint and gasoline, that defined how much privacy a landlord needs to give his tenants, and that determined how much a phone company can surveil its customers. We can decide how we want to handle digital surveillance, attention-channeling, harassment, data collection, and algorithmic decisionmaking. We just need to start the discussion. Now.”

Designers are in a unique position to shepherd that discussion. We are systems thinkers, communicators, and we should also be stewards of ethical design, even when the design in question is at an architectural level. It is our duty to be informed and to care even when things are out of our control, and to support efforts where we can, like Tim Bernersl-Lee's Solid project at MIT, which aims to re-decentralize the web by giving people full control over how their data is used. As Tristan Harris says, we need a “design renaissance” to imagine the world we want to live in before we can create it.

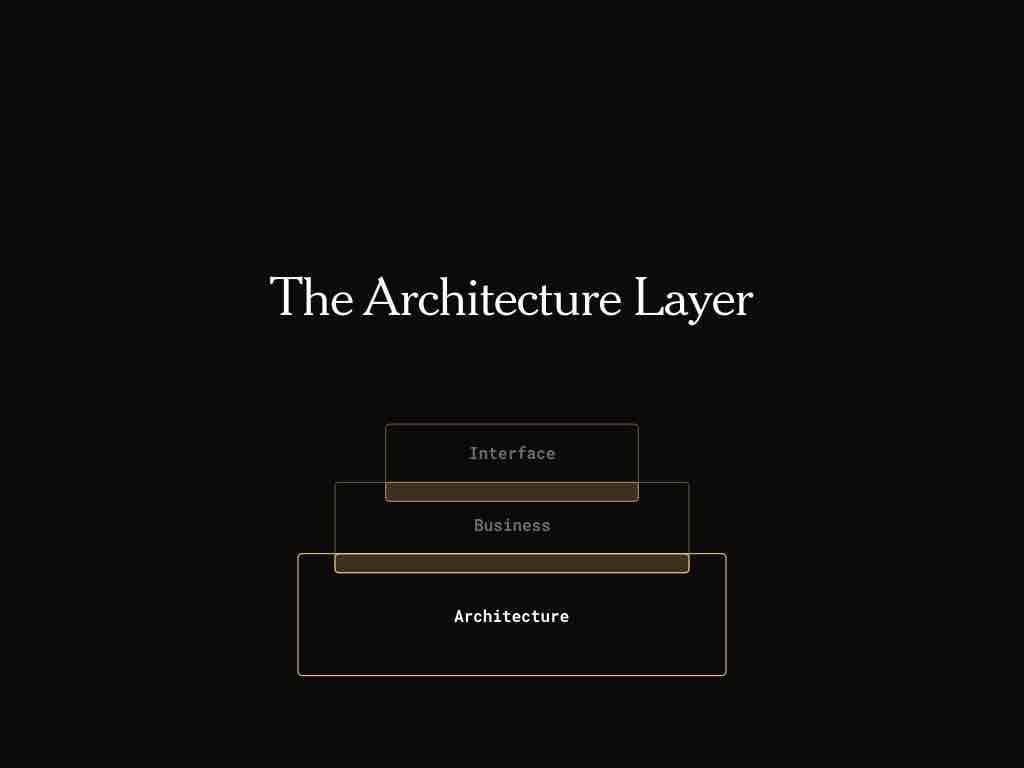

Let’s move up a step. On top of the architecture layer is the business layer. This is the level where decisions are made about digital things: What does our product do? How does it make money? What customer needs does it fulfill? How is it moderated and managed? Every organization shares the same web architecture constraints, but they all follow their own strategies and tactics to survive in the marketplace.

This is the level where designers get a little more say in how things are done. Some organizations might be more design-oriented, empowering people with “design” in their title to make product strategy decisions that affect the direction of the business. Other organizations might treat design as an interface veneer on top of business requirements. Either way, designers have a certain level of influence here on digital objects.

And what’s important for us today about this level is that this is where business values get embedded into products and websites and platforms. It can’t not happen. They can be subtle or obvious; either way, designers inscribe values into technologies.

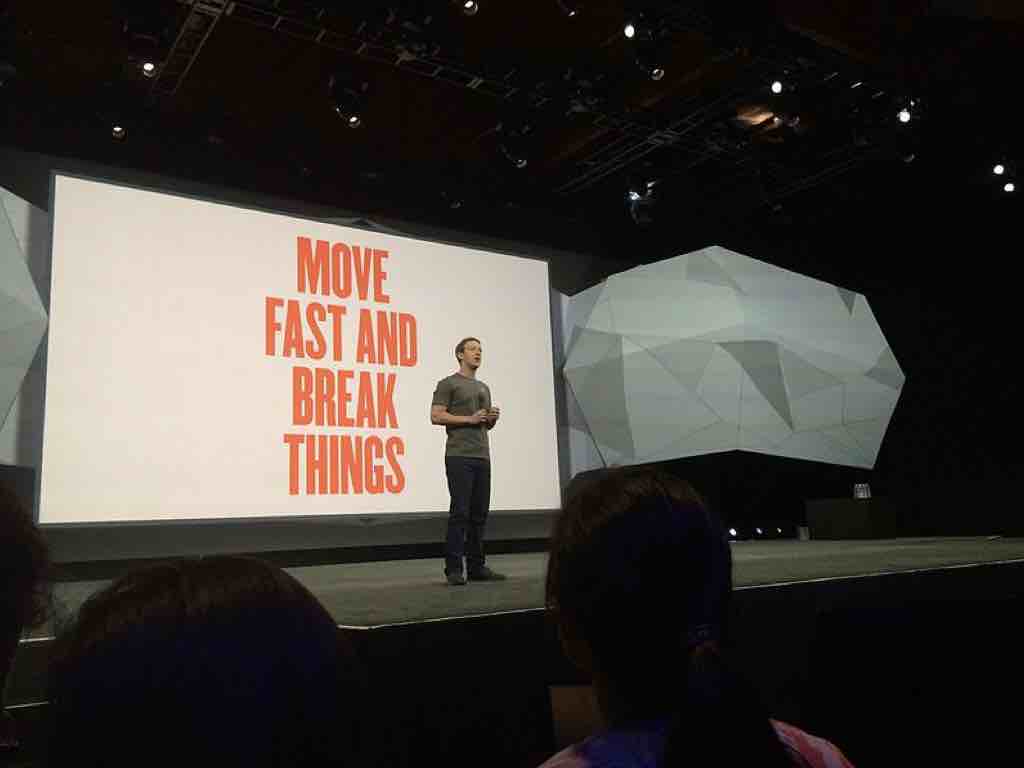

I picked on Facebook a little earlier, and I'll do it again here. Their original slogan — “move fast and break things” — went out of fashion after they moved quickly and broke a lot of things. But that’s still how they operate as an organization. Facebook values speed, novelty, reach, connectedness, efficiency, and time-on-site at the expense of lived human experience.

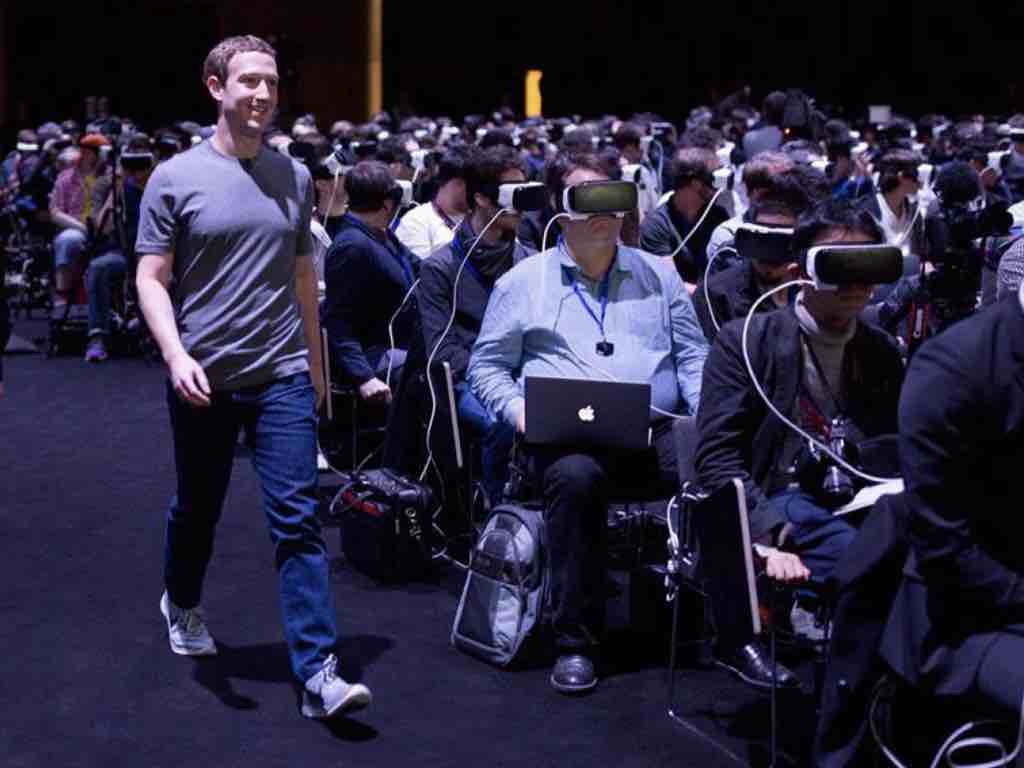

They’re experimenting with immersive AR and haven’t even begun to solve issues with online harassment. This should give us pause. (Sidenote: Oculus' founder, Brendan Iribe, just left Facebook, taking cues from the recent departures of the WhatsApp and Instagram founders. Facebook still owns the technology, though.)

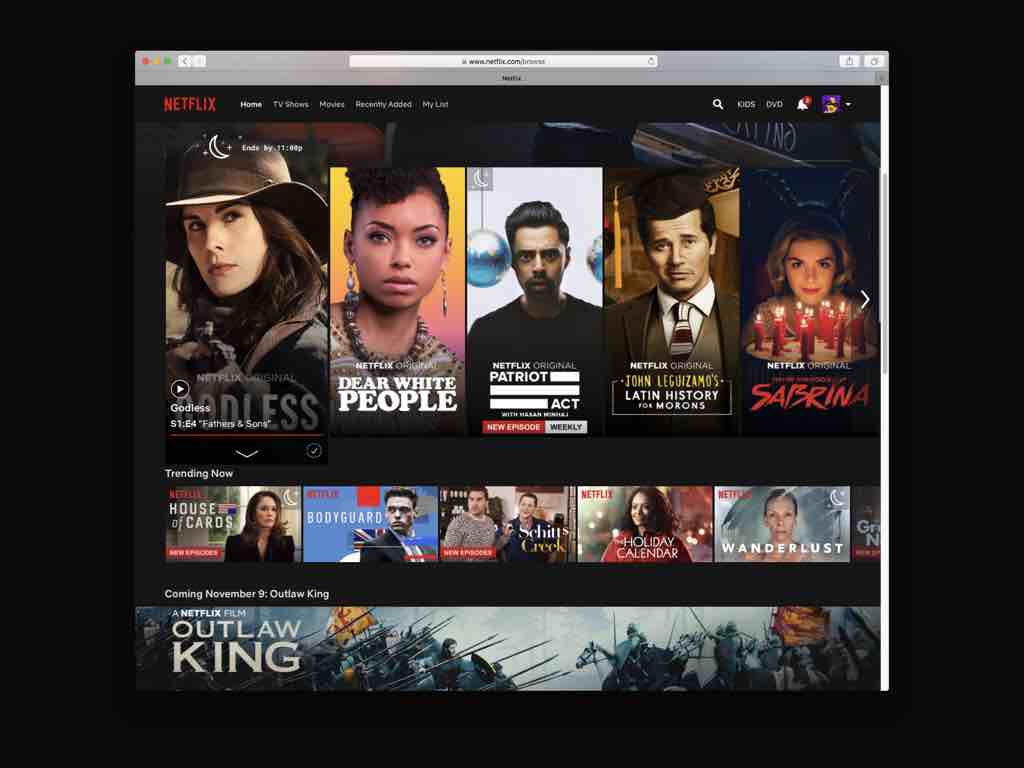

Or take Netflix. Know who their CEO, Reed Hastings, sees as their main competitor? Not Hulu or HBO.

It’s sleep. And this kind of makes sense, sort of. They’re the global leader in content streaming. And people fall asleep when watching auto-played shows at night. What if they chose to respect sleep as a human limit?

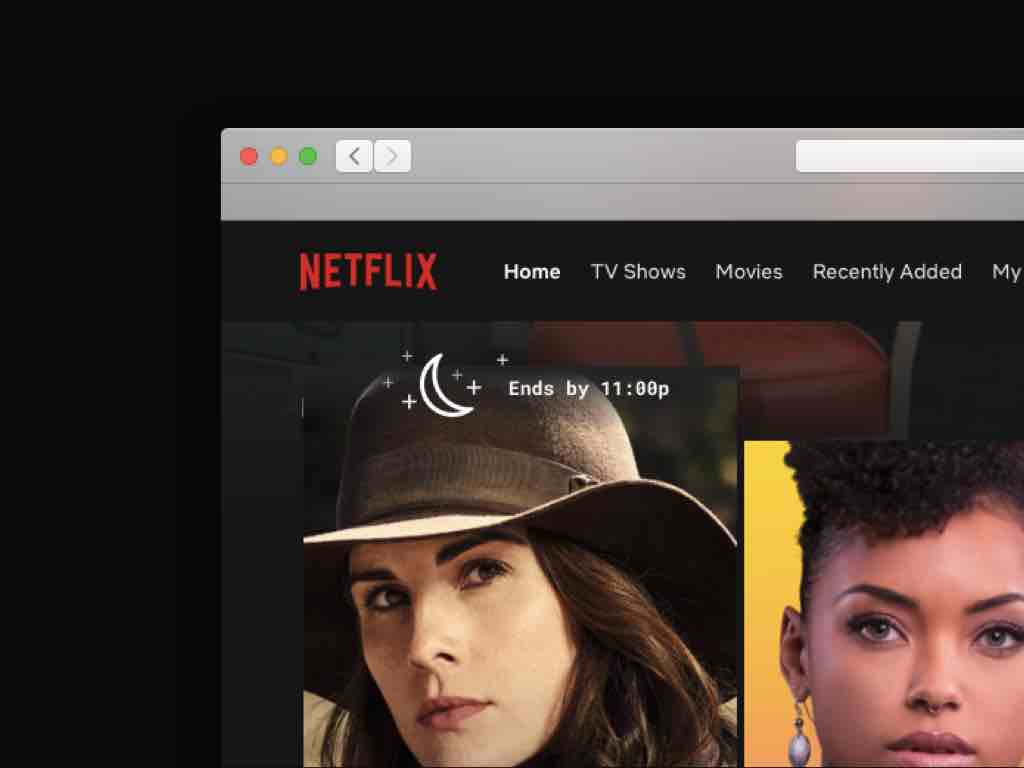

What if you could set your bedtime in Netflix to see what movies or shows you could watch and still get to sleep on time? My coworker Dave came up with this idea.

Maybe you'd see little icons for movies that match the bedtime you set for yourself, and a nice detail on hover.

The folks at Humane Tech encourage designers to “reimagine their products with clear-eyed understanding of being human, and compassion for our vulnerabilities and needs.”

They show how Google maps could suggest transportation options based on fitness goals that you set.

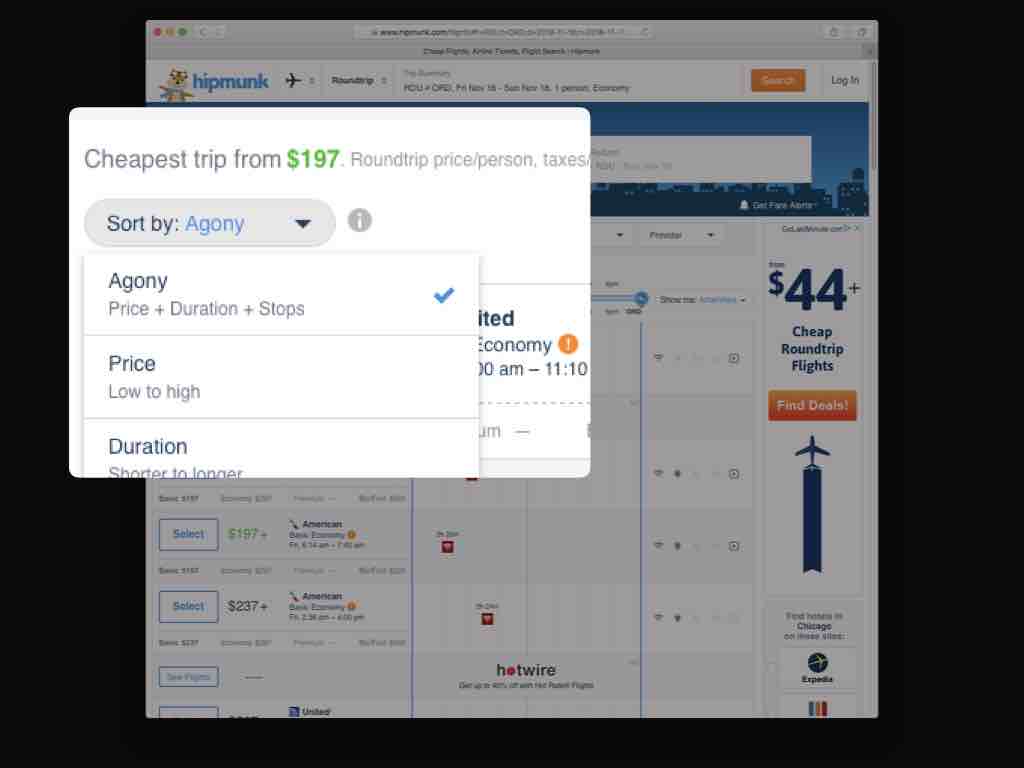

And here’s one of my favorites: Hipmunk’s “agony” filter for selecting flights. It accounts for time of day, layovers, and the like. It’s a small thing, but show’s that they’re considerate of the real human experience of traveling.

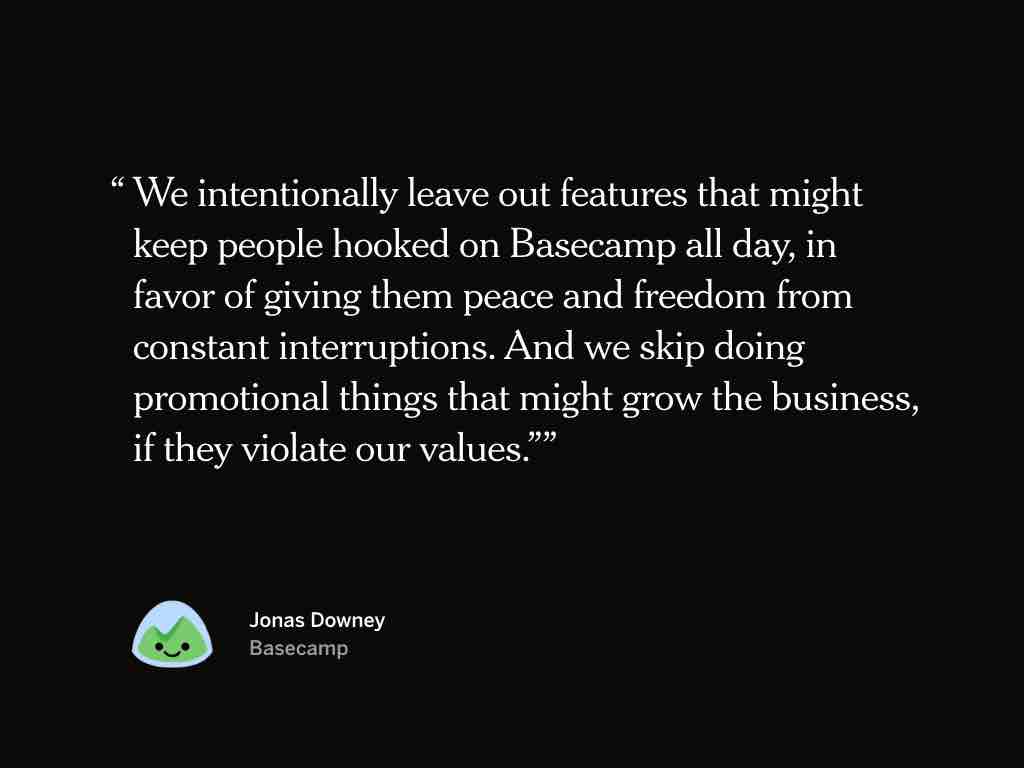

Basecamp’s products aren’t perfect, but I appreciate their attempt to build based on human values. In particular, they try to help people stay in control of their time and attention and leave work at work. In his post, “Move Slowly and Fix Things,” designer Jonas Downey describes their approach:

“We design our product to improve people’s work, and to stop their work from spilling over into their personal lives. We intentionally leave out features that might keep people hooked on Basecamp all day, in favor of giving them peace and freedom from constant interruptions. And we skip doing promotional things that might grow the business, if they violate our values.”

They’re trying to build what might be called “calm technology.”

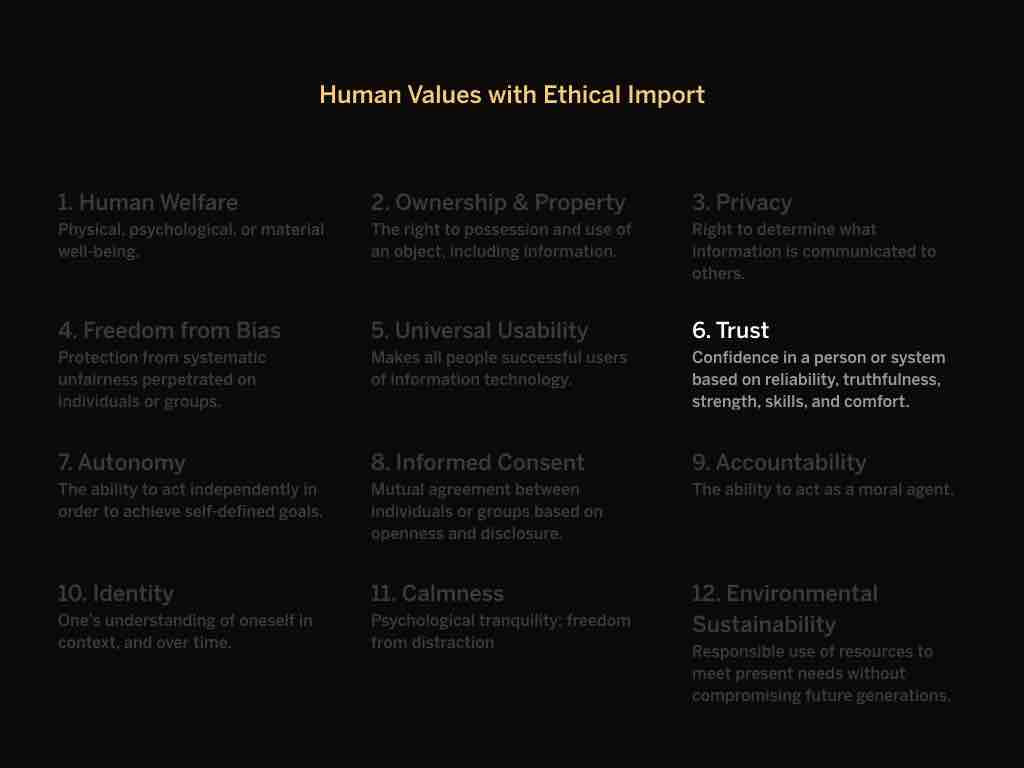

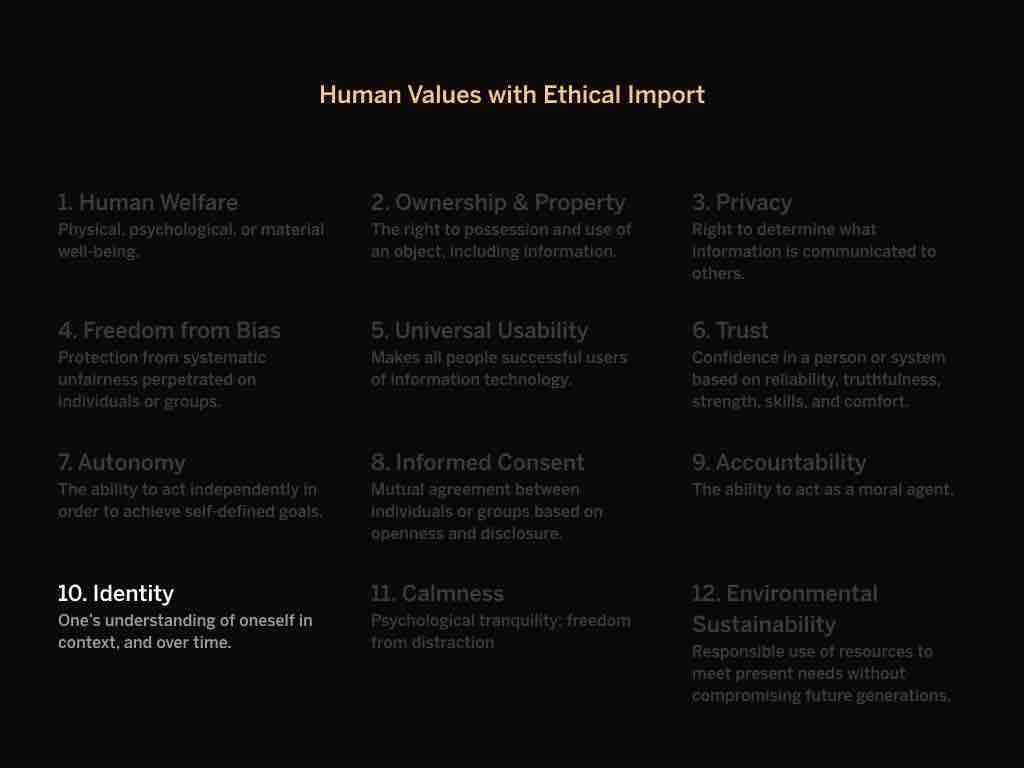

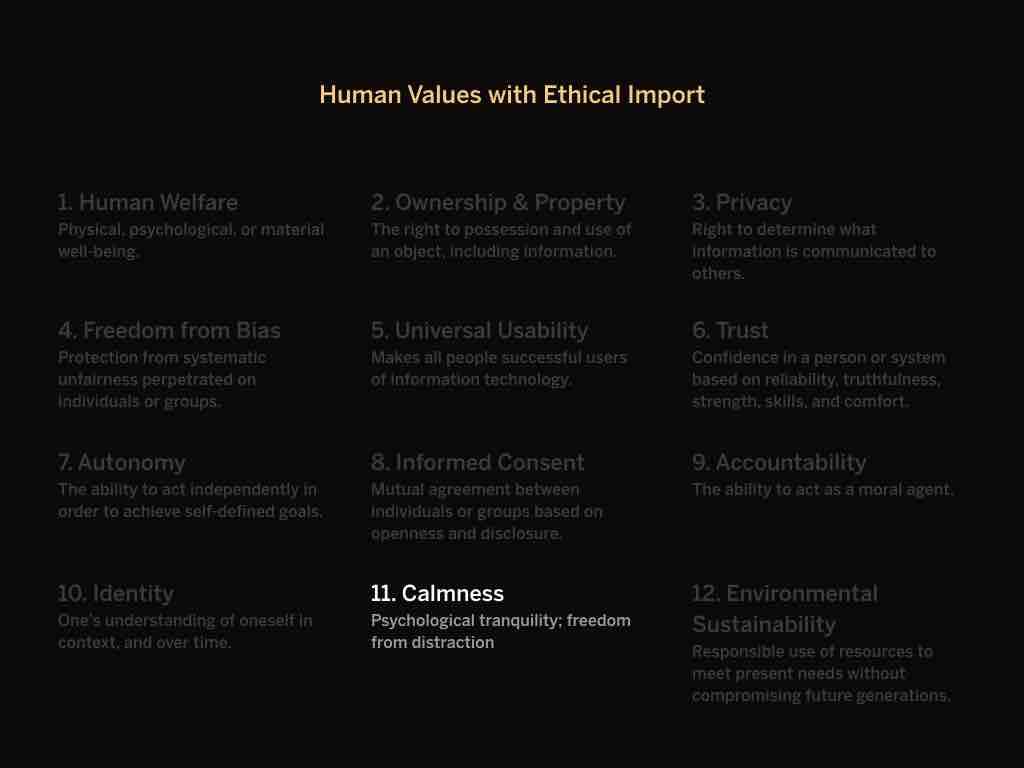

We need to be aware of the values we are inscribing into our technologies. A good place to start is with this list of twelve, called the “human values with ethical import.” Things like human welfare, autonomy, respect, freedom from bias.

We take many of these values for granted as conscientious designers. But they can serve as a rubric for evaluating designs. Remember, ethics is the act of evaluating actions in context.

Take trust, for example. We trust someone when they reliably treat us fairly and respectfully. In an interface, this means that buttons do what we expect them to when we click them, or content is clear and up-to-date. Many dark patterns take advantage of people’s trust by using a common interaction pattern in an unpredictable way.

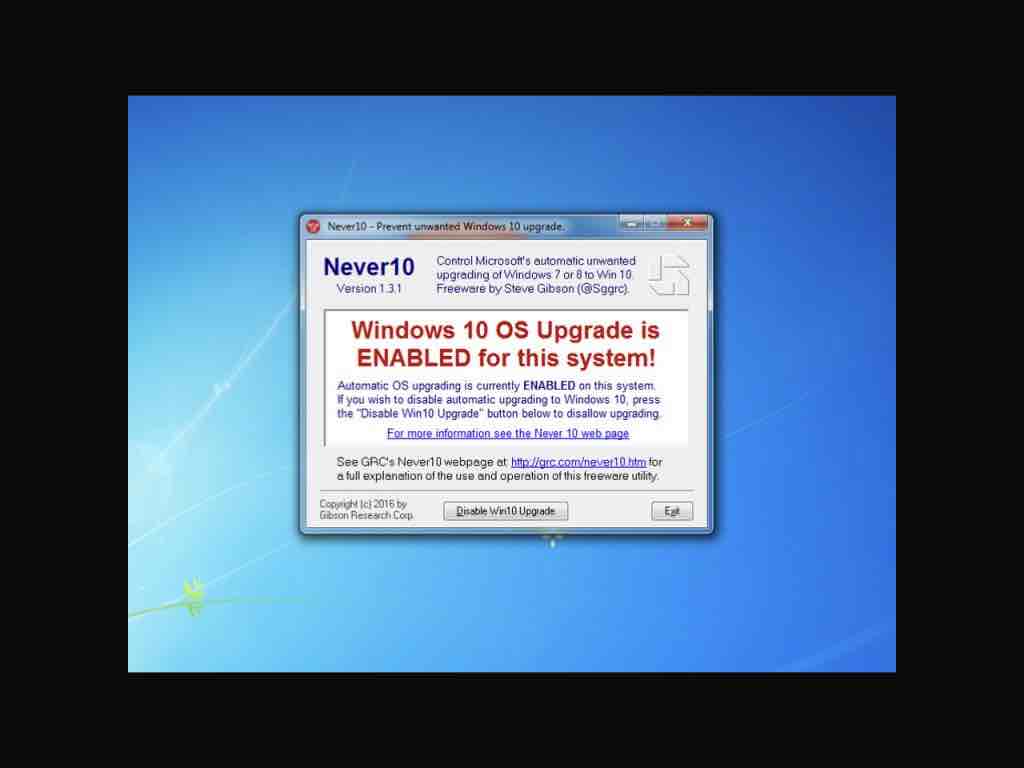

Like the Windows 10 Modal a few years back. Normally, when you click a “close” link in a modal, the modal closes and you cancel the action. Microsoft was getting impatient with people who weren’t upgrading, though, so they ended up changing the behavior of the close link. Instead of hiding the modal, clicking “close” agreed to the update. The technical term for this is a bait and switch.

I like what one commenter said about this: “It’s like going out to your car in the morning and discovering that the gas pedal now applies the brakes, while the brake pedal washes the windshield. Have a fun commute!”

The value of identity is a little less obvious. It has to do with the way that people are represented in digital systems. Psychologists remind us that our personalities are unified and multiple. I am one person, but I am a slightly different person at work than I am at home, or when hanging out with my brother, or when walking my dog through the woods.

What we need to always keep in mind is that digital representations of people are inherently reductive. People cannot be fully represented by a system, digital or otherwise, because they are being represented on the system’s terms. We inherently know this. Our Facebook or Instagram or Medium profiles only show a little of who we are.

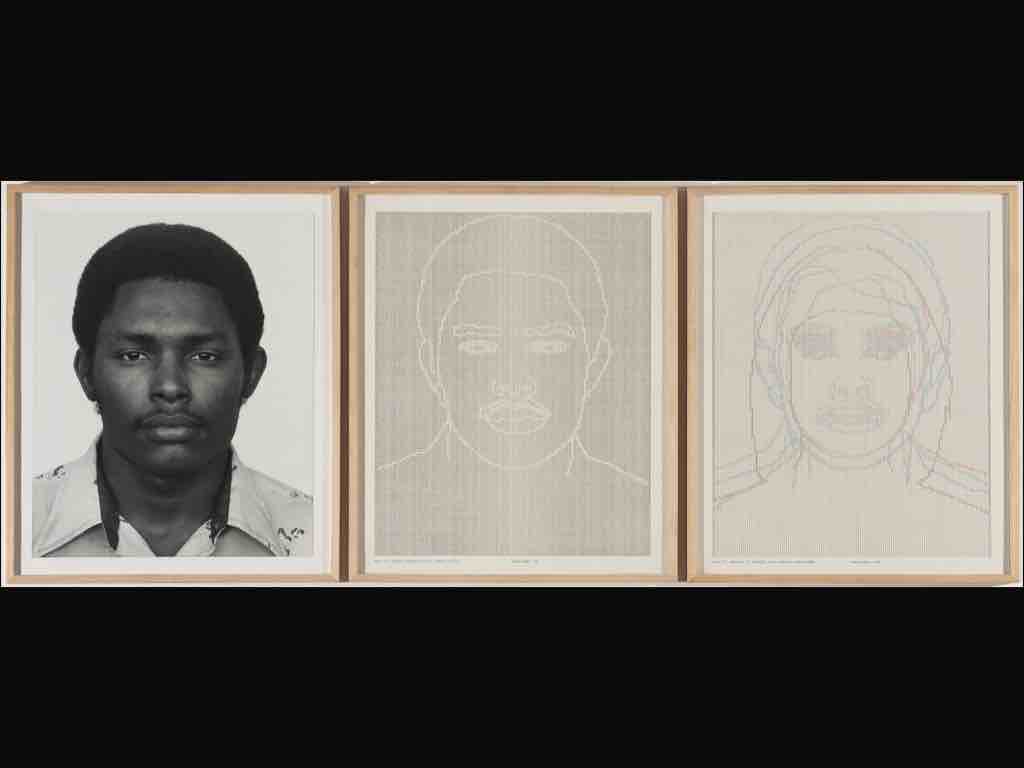

Charles Gaines dealt with this in idea in his paintings in the 70s. He would take a photograph, then begin abstracting it to show how systems distort people and things even as they try to represent them. They “objectified people beyond recognition,” to use the words of one commentator.

Sometimes the digital things we make our beautiful. But we can’t forget that we are making systems that represent real people and things. It’s up to us create systems avoid reductiveness to the extent that they can. To allow ambiguity and fullness of expression and representation. This is obviously a complex thing to accomplish.

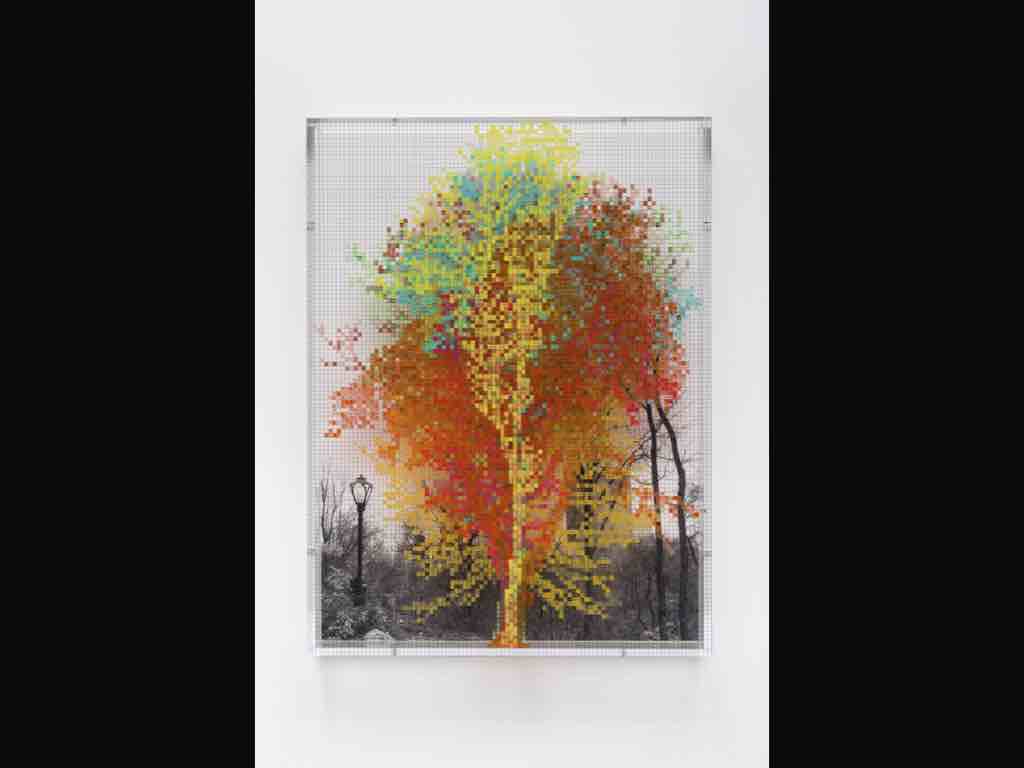

Let’s look at one more value: calmness. At this point in the game, we’re all growing tired of our devices shouting at us. We’re getting better about this as a society: you don’t hear ringtones very much anymore in public (though they can still be handy). And alert settings have improved, with things like Do Not Disturb mode.

Alerts are an annoyance on our devices, but as we move into an era of ubiquitous computing, where computers are embedded into environments, alerts and notifications can become serious issues. We need to learn to make technology that remains passive and peripheral, announcing itself only when absolutely necessary.

A few years ago, appliance companies realized that refrigerators didn’t have screens on them yet, so they fixed that. Now you can buy a fridge with a monster iPad embedded into it. We heard you liked iPads.

So myself and a few designers at Viget worked on a design concept that thought about what it would be like for appliances to have screens but remain unobtrusive. Instead of letting you check your email while filling up a glass of water, how could a refrigerator interface preserve the ways people currently use their refrigerators? What if we didn’t try to co-opt the space by slapping an iPad on it?

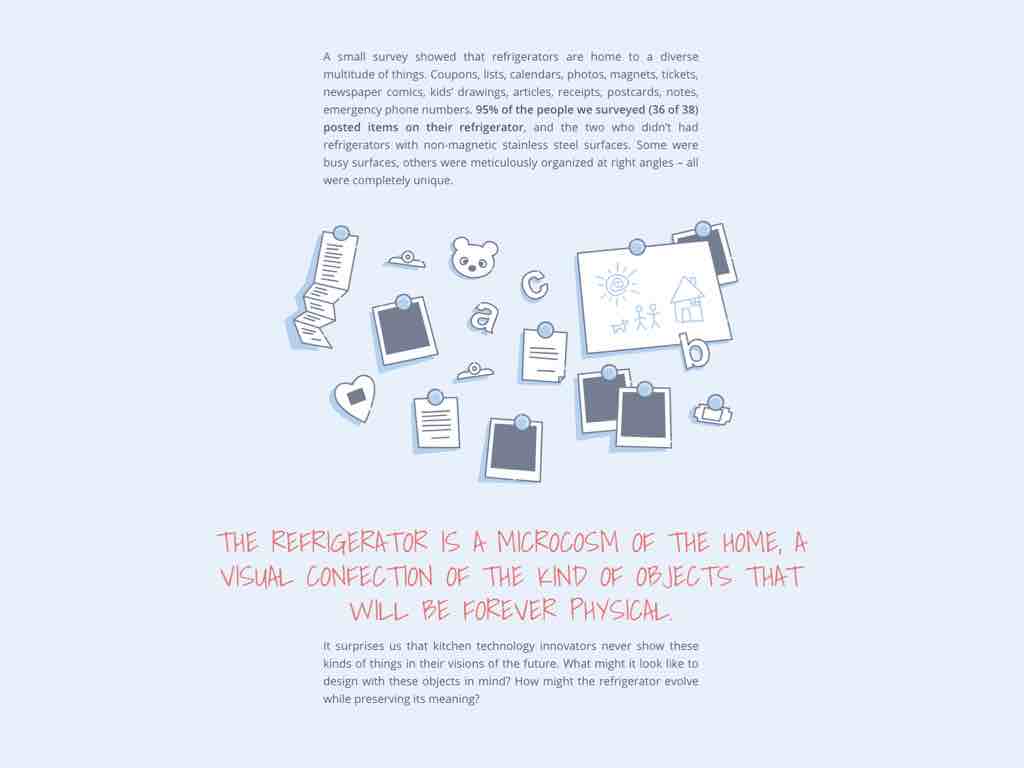

We asked people to share pictures of their fridges, and saw exactly what you’d expect: pictures, clippings, kids’ drawings, weird magnets. Refrigerator surfaces are perfect for what they’re used for. They were folksy and cute and unique in ways the standardized screens can never be.

So we thought about how a display could still allow people to post physical objects, but draw next to them on a digital e-ink display. E-ink is a lovely technology: it’s easy on the eyes in the way LED screens aren’t, and remarkably energy efficient. We tried to design an interface that remained peripheral to the life of the family.

There’s a lot to think about here. If you’re interested in a deeper exploration of the topic, I recommend reading this paper, “Human Values, Ethics, and Design” by Friedman and Kahn. And it occurs to me that designers can fail these values intentionally, like when they design disrespectful UIs, but they can also fail them out of laziness, or negligence.

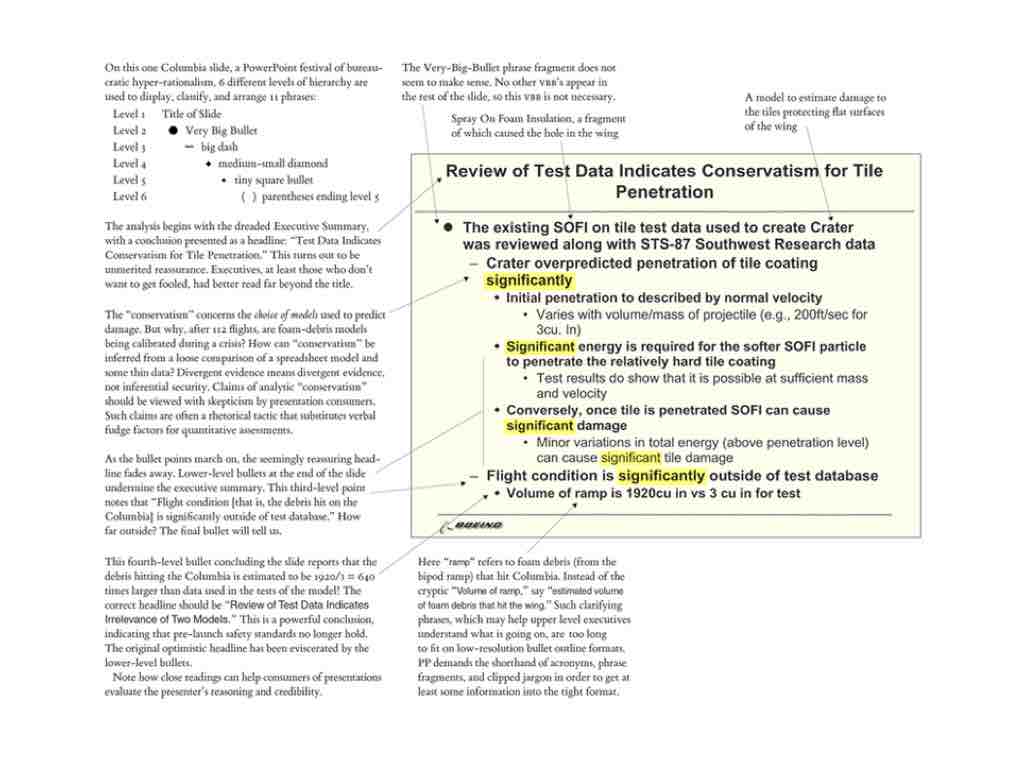

A number of catastrophes have occurred as a result of negligent design. Patients don’t get the appropriate dosage they need. Critical information is obscured by the way it’s presented. Edward Tufte makes the argument that the Apollo 11 disaster can be traced back to the PowerPoint slides used to convey mission-critical risks. Design decisions can become life-and-death decisions.

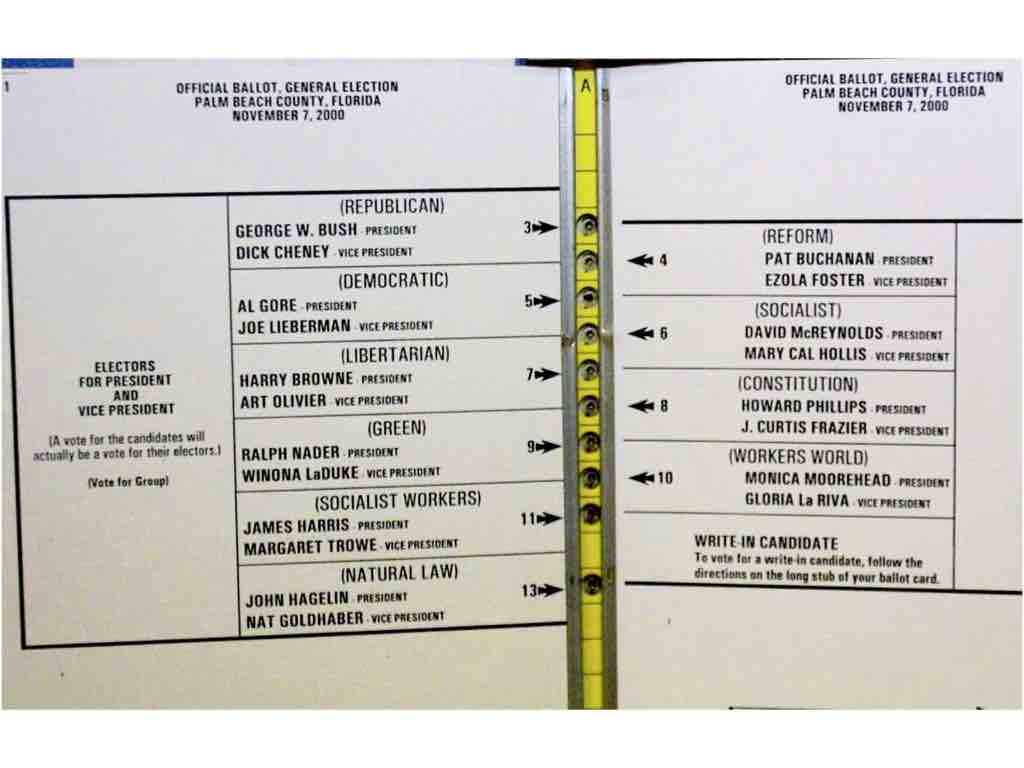

And we all remember Florida's 2000 election ballot. The design influenced the vote. Zeynep Tufecki has pointed out that the way Facebook designs its voting event notifications influences voter turnout. This should also give us pause.

Thankfully, not all of our decisions carry that much weight.

And if you’re negligent in the right ways, you might even earn some cool points. Normcore web brutalism is all the rage these days.

So we try to be intentional about what we do, but sometimes we struggle to think beyond the screens we’re designing — to value impact over form, in Mike Monteiro’s words. And usability testing doesn’t guarantee this kind of consideration. People aren’t just opening our websites in usability labs; they’re looking at them while distracted at the grocery store, or in a moment of crisis. Eric Meyer has written about how designing for emotion doesn’t just mean designing for delight; in fact, sometimes it means the opposite: delight may be a completely inappropriate goal in certain contexts.

And in order to value impact over form, we need to develop what the philosophers call our moral imagination. To imagine the ethical consequences of our designs. To see the values we’re inscribing. And we need to help others do the same.

For most of us, our company’s or clients’ values correspond with our own. But what happens when they don’t? UXers are in the position of negotiating business needs and people’s experience. Sometimes this feels like an irresolvable tension; we’re trying to do right by our users while still accomplishing business objectives. Sometimes design gets bullied by business into doing things it doesn’t want to do.

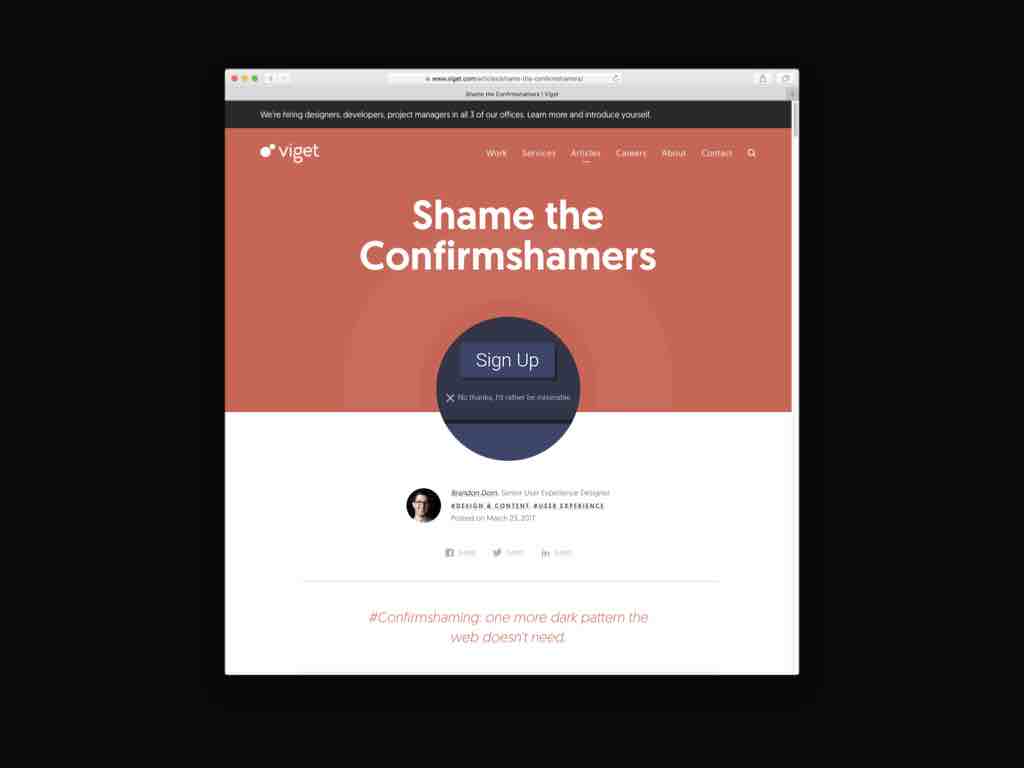

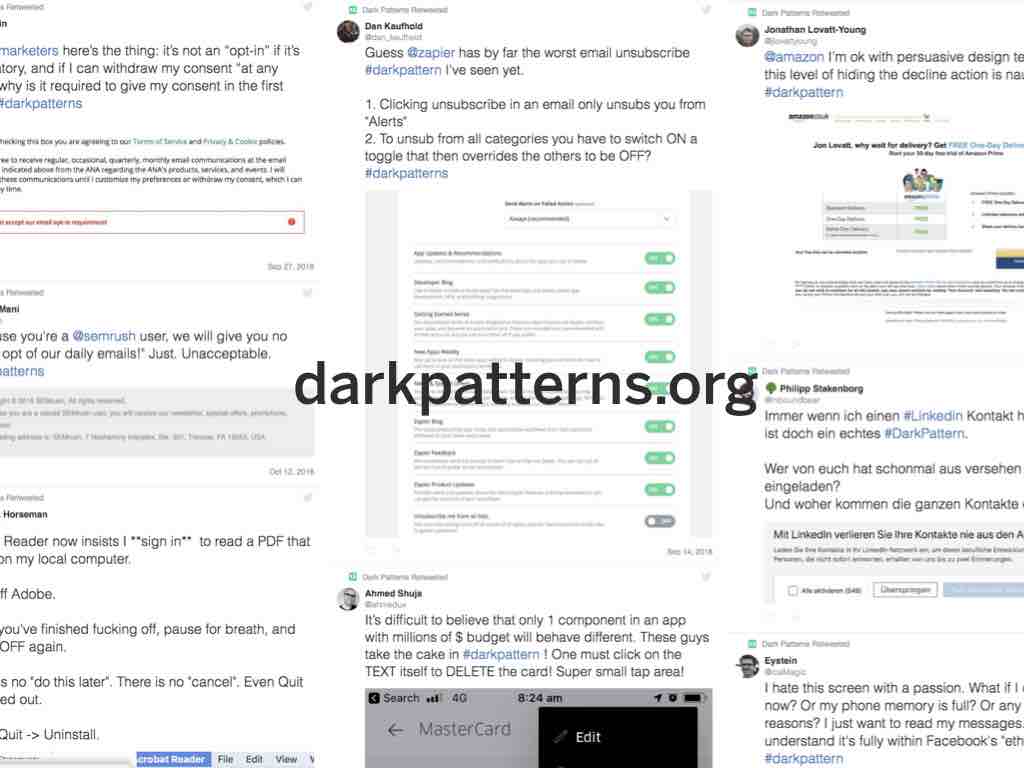

Jonathan Shariat, who wrote the book Tragic Design, gives examples of how designers can become ethical voices in their organizations. For one, it can be meaningful simply to name dark patterns when we see them. This is confirmshaming. That’s a bait and switch. That’s misdirection. Naming things forces them out into the open, and requires discussion and kind correction, when necessary. “This is a thing, and it’s bad, and here’s what we risk.”

He also suggests using analytics to show the consequences of manipulative design. He talks about a time when his company decided to charge subscribers after their free trials ended, without their consent (technically called “force continuity”). The numbers showed that the subsequent deactivations far outweighed the initial signups, not to mention damage to brand perception. We need to consider how to frame ethical problems as business problems.

But sometimes companies profit massively by going against their stated values. Google employees petitioned against Google’s bid for a Pentagon contract by pointing out how the company would be violating its beliefs. Microsoft employees did the same. Google withdrew, though Microsoft hasn’t yet. This is another weighty example.

But the point I want to make is that designers have a role to play as ethical safeguards in their organizations, UXers especially. Not that we should go looking for ethical issues where they don’t exist, splitting hairs about color usage and the like. But at the heart of UX is concern for real people using technology.

This will continue to become an increasingly important aspect of employees' consideration as we deal with the consequences of our technology.

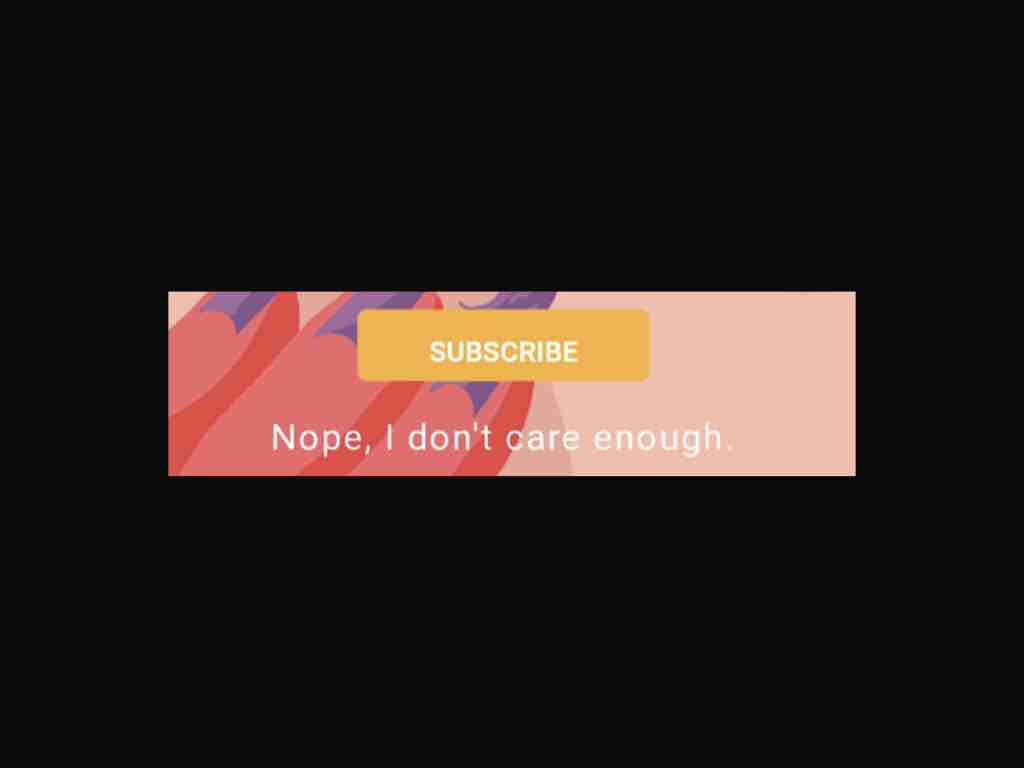

Confirmshaming is a small example where we can take a stand. I’m sure you’ve seen these modals. Subscribe to our newsletter? “Yes!” Or, “No, I’m an idiot.” People are still doing this nonsense.

”I love losing customers!” Of course.

“I just don't care enough to get more spam...”

“Save money? Are you kidding me??”

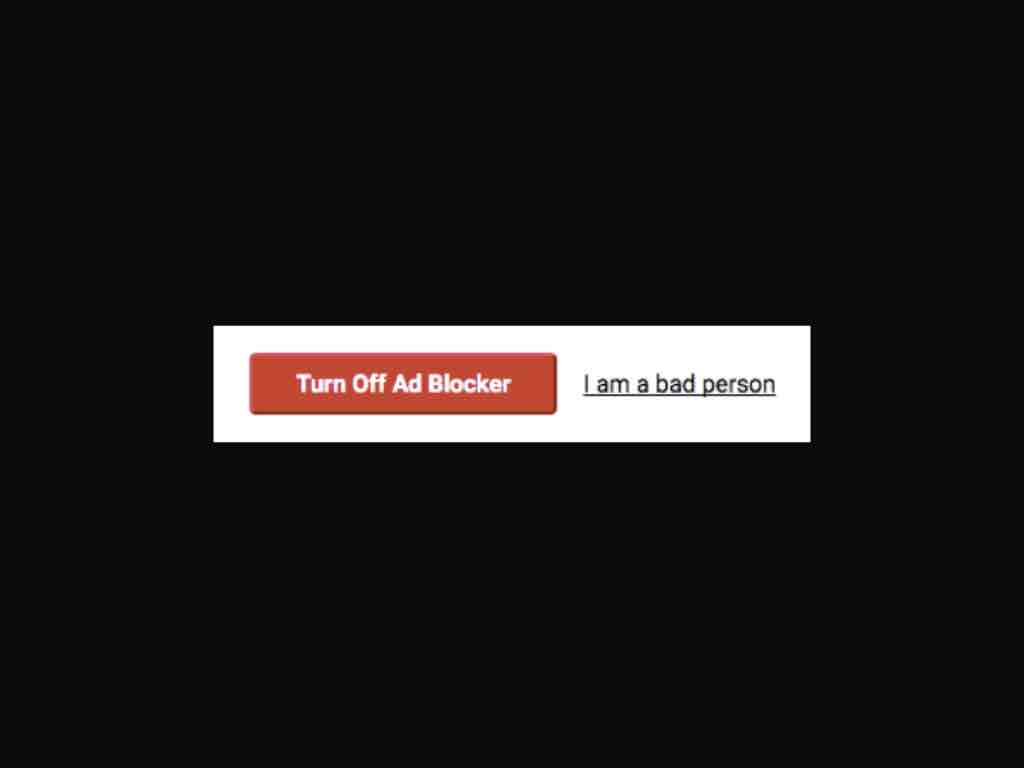

”I'm just a straight up bad person.” At least they aren't trying to be subtle?

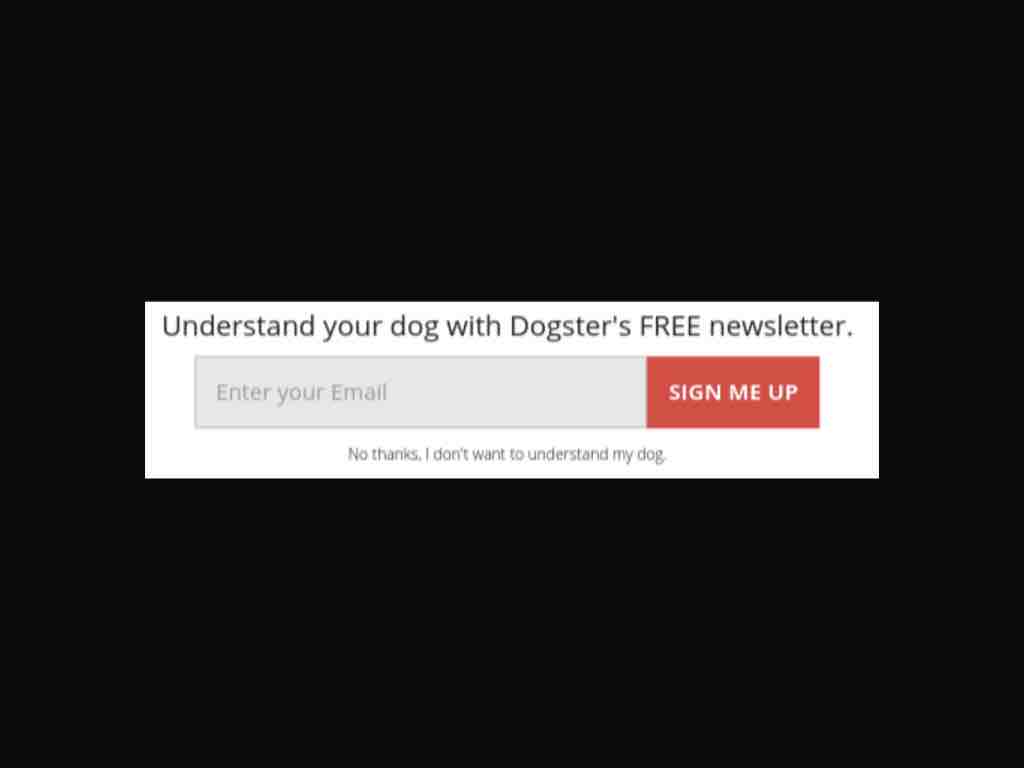

”I don't want to understand my dog...” I'm not sure I‘ll ever understand my dog.

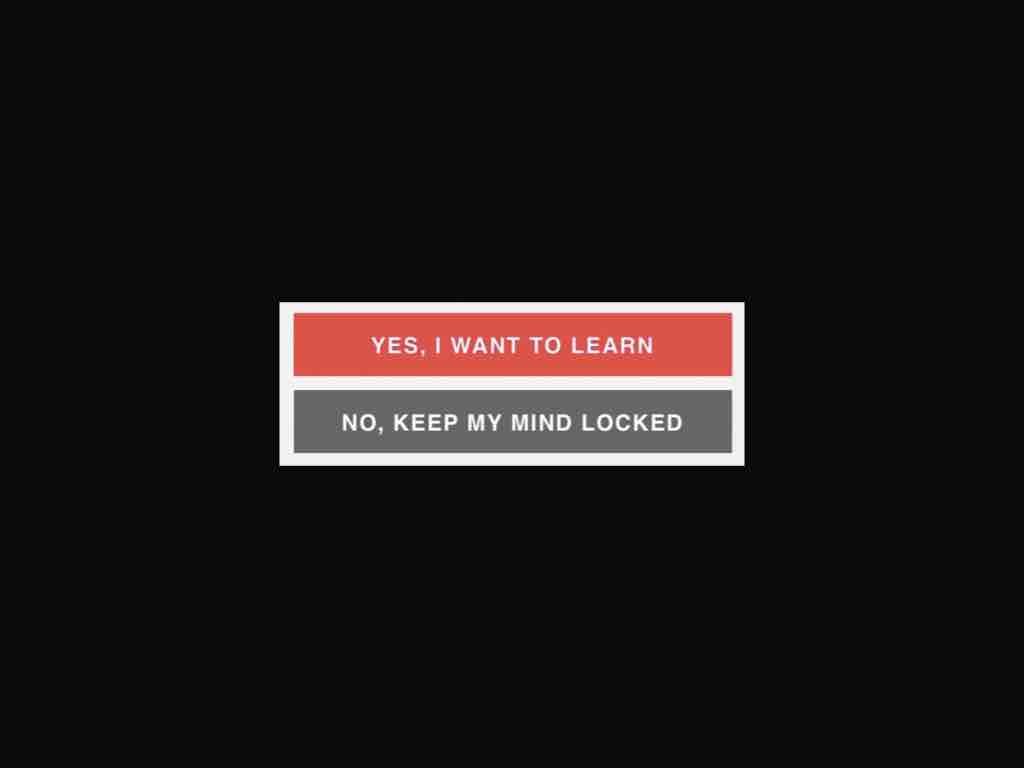

This one‘s my favorite: ”KEEP MY MIND LOCKED.”

Last year I wrote an article criticizing this trend, and someone responded to my post by claiming that confirmshaming must be working if websites are using them. He complained that I didn’t offer a viable alternative. I responded by saying that the alternative is to do the hard work of learning about your audience and producing better content. (He didn't write back.) There’s no shortcut to growing a sustainable, dedicated user base. Nearsighted, desperate tactics like these mask deeper issues that businesses need to solve in order to remain viable in the digital age.

Sometimes design issues are business issues in disguise. Sometimes design masks business insecurities. And the truth is that design cannot solve a business problem.

And as designers, we need to be direct about things like this. And if you can’t stand up to a client or stakeholder about something this small, you’re abdicating your ethical authority. We can’t be afraid to use the language of good and bad.

I haven’t talked much about the interface layer today, and that’s because I don’t think this is where the real problems are for the kinds of conscientious designers who would spend an hour listening to a talk about design ethics.

If you walk away with one thing today, it’s this. Usability isn’t enough. Accessibility isn’t enough. We have to ask if what we’re making is good. We have to question the ends to which we are making things.

Because unfortunately, we’ve lost our way. UX has contributed to many of the problems we see today with addictive technology and the attention economy. User-centered design and “designing for delight” have been co-opted to keep people “engaged.” “Don’t make me think” has turned into “Keep me from thinking about what I’m doing.” “Keep me from weighing the costs.” I’m read this quote from Cennydd Bowles in full, because it’s good.

“The strategies that create desirable products also foster addiction….That we find it difficult to tease apart addiction and desire speaks to the failure of the experience design movement. Designers haven’t interrogated the difference between enjoyable and habitual use, and the rhetoric of designing for delight has directly contributed to addiction” (Future Ethics).

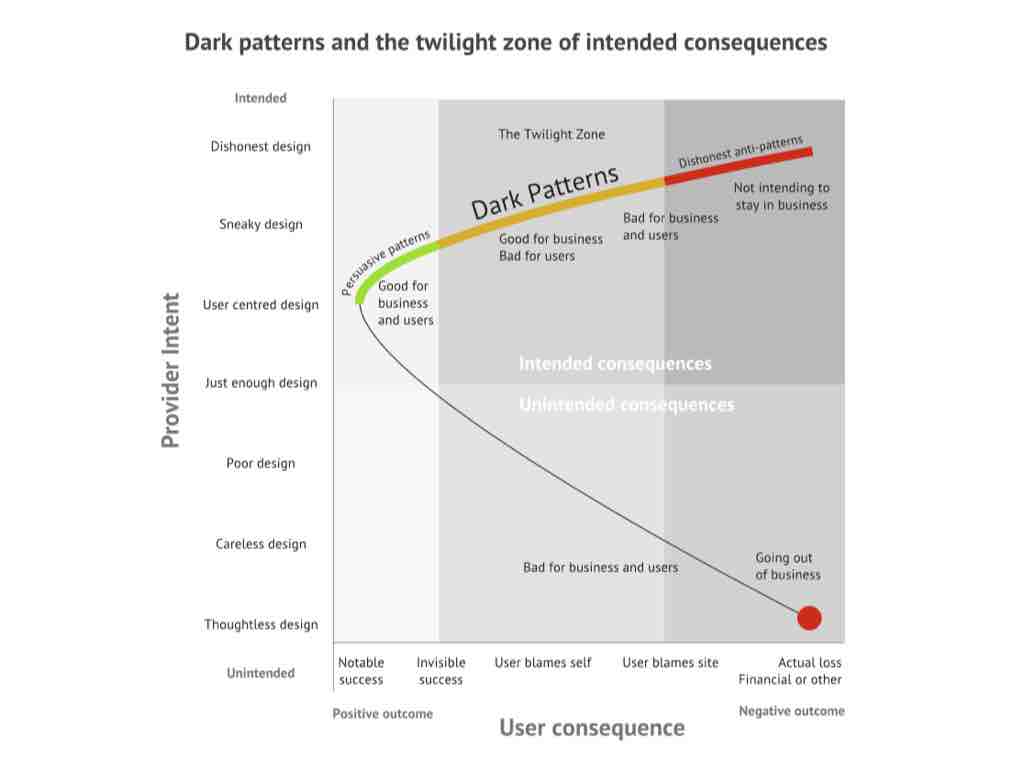

I struggle with this because I know it‘s true, but most of the time I’m just trying to help clients get to usable. I’m trying to get them up here (left quadrant), into healthy persuasive patterns. Usually they’re somewhere down here in this danger territory. But they aren’t up here, dangerous enough to manipulate people, or insidiously trying to co-opt their attention. But someday they might be, and I want to help them think critically about what they’re after. We need to think critically about the ends to which our methodologies are being used, and teach young designers to be critical too.

We need to hold each other and organizations accountable for their designs. But we also need to keep in mind that when we talk about things at this level, we’re talking about symptoms, not causes.

So, this has been an admittedly broad conversation. We are talking about ethics after all. So let’s get practical.

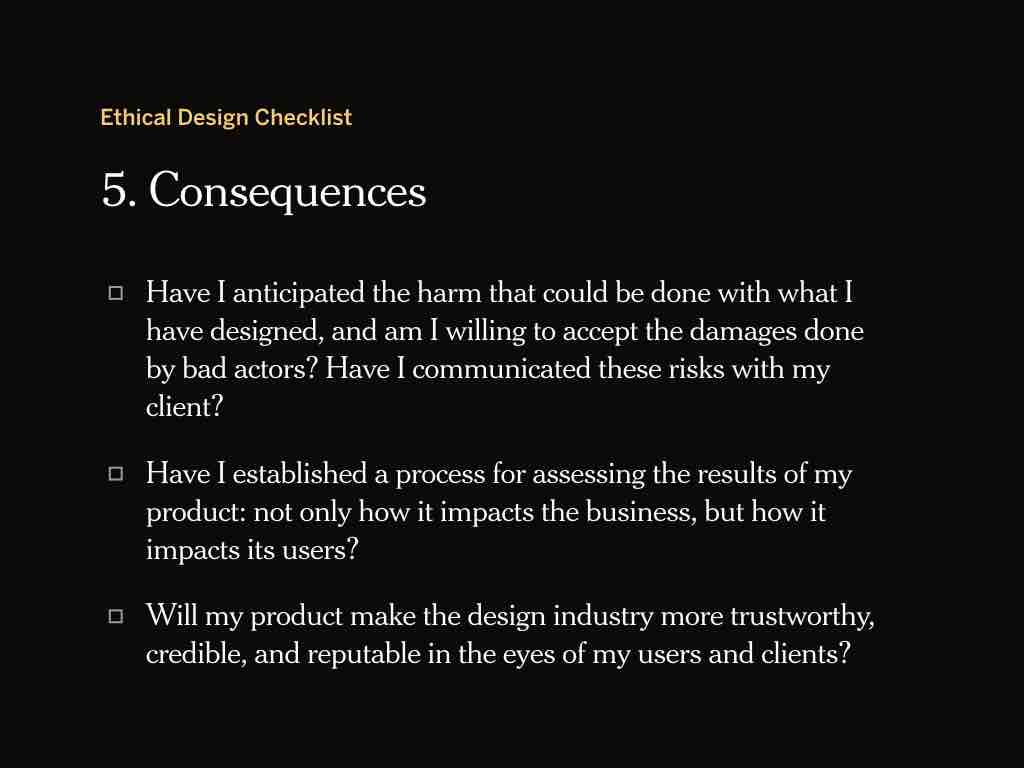

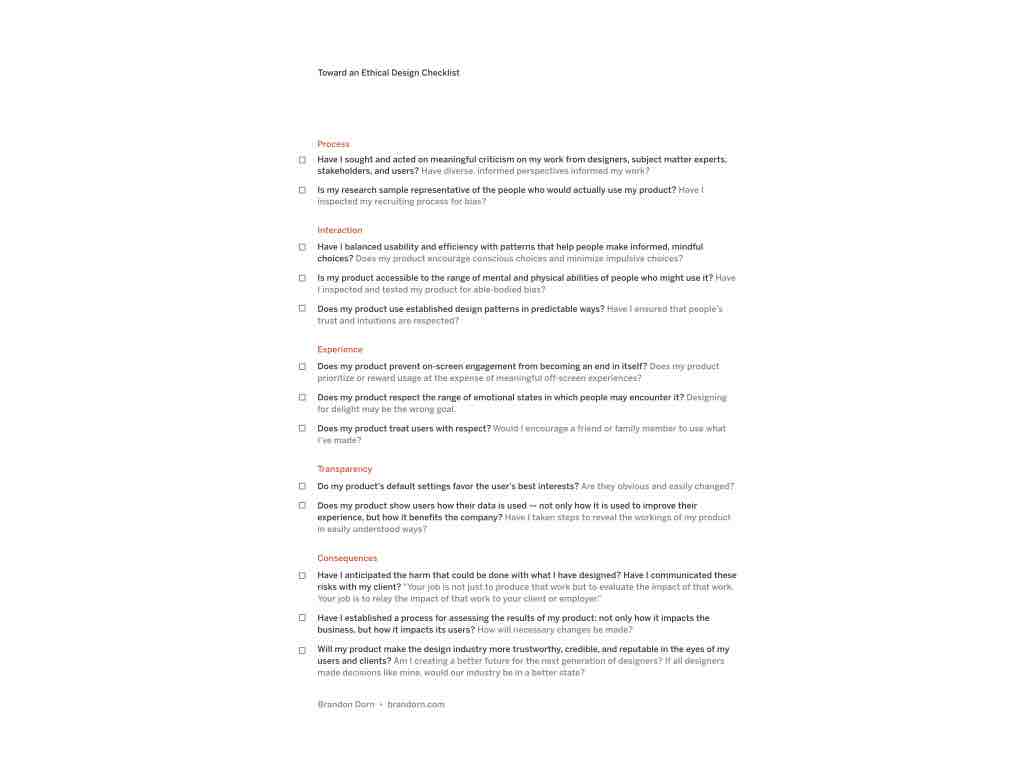

The risk with a checklist is that ethics becomes a box to check rather than a pervasive mode of thinking. A four-hour meeting rather than a robust, critical culture. Yet if our ethical thinking doesn’t have practical implications, we might as well not have conversations like these at all.

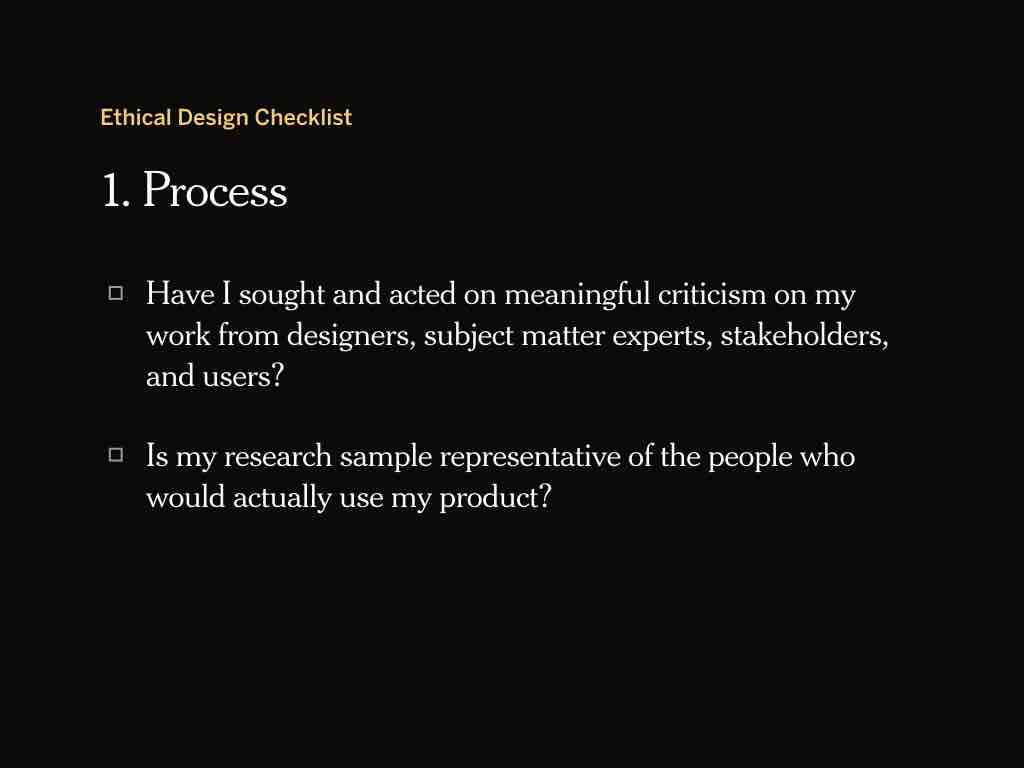

Having a checklist is based on the idea that a concise list of validation points is more effective than a one-time oath. Here is an example of what an ethical checklist might look like.

When it comes to process, have I sought and acted on meaningful criticism on my work from designers, subject matter experts, stakeholders, and users? Have diverse, informed perspectives informed my work?

Is my research sample representative of the people who would actually use my product? Have I inspected my recruiting process for bias?

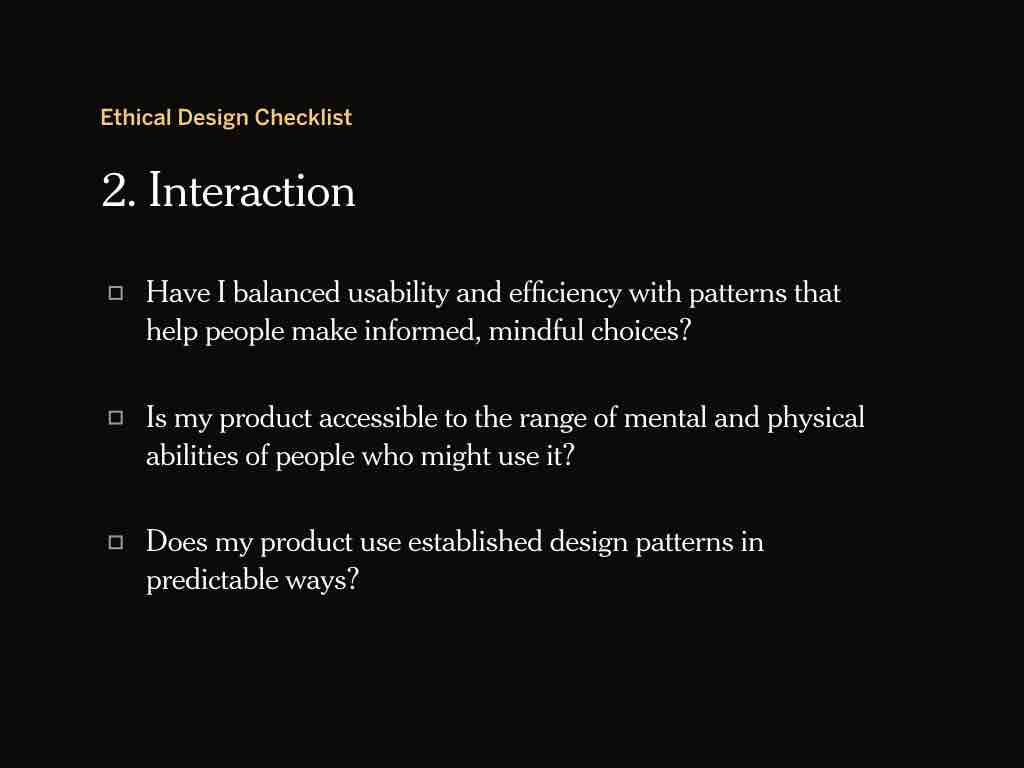

Have I balanced usability and efficiency with patterns that help people make informed, mindful choices? Does my product encourage conscious choices and minimize impulsive choices?

Is my product accessible to the range of mental and physical abilities of people who might use it? Have I inspected and tested my product for able-bodied bias?

Does my product use established design patterns in predictable ways? Have I ensured that people’s trust and intuitions are respected?

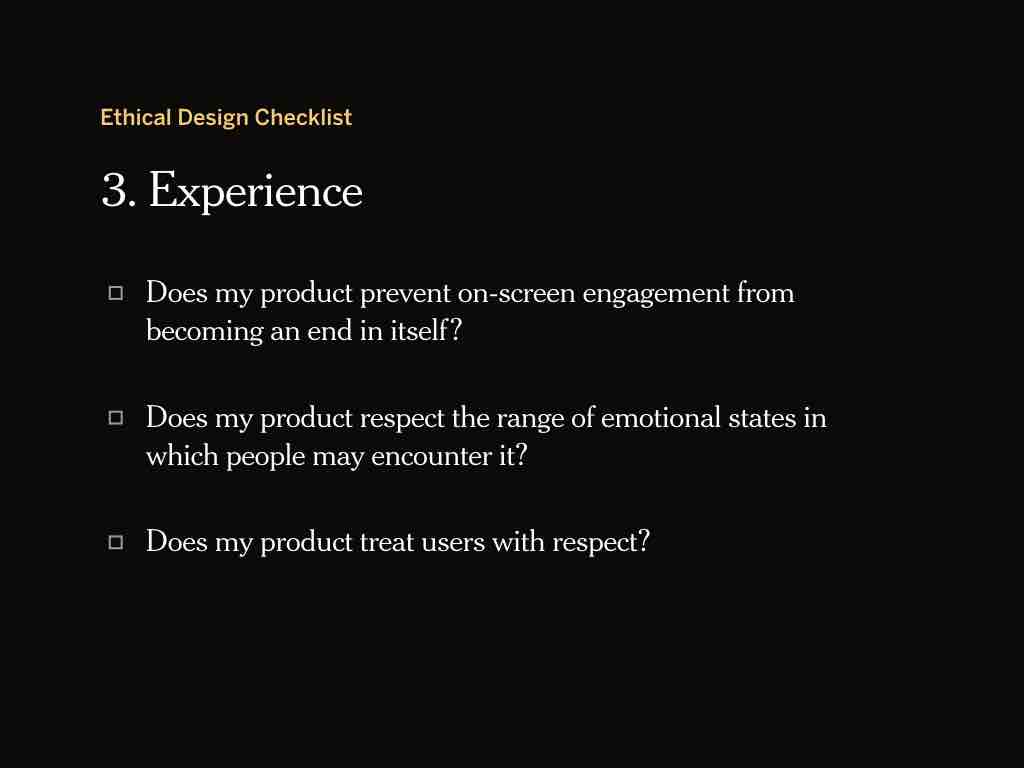

Does my product prevent on-screen engagement from becoming an end in itself? Does my product prioritize or reward usage at the expense of meaningful off-screen experiences? The folks at the Center for Humane Technology encourage us to ask if our products help people remember what they really want to be doing — not just using our product — and if the way we design things like alerts make it easy to disconnect.

Does my product respect the range of emotional states in which people may encounter it?

Does my product treat users with respect? Would I encourage a friend or family member to use it?

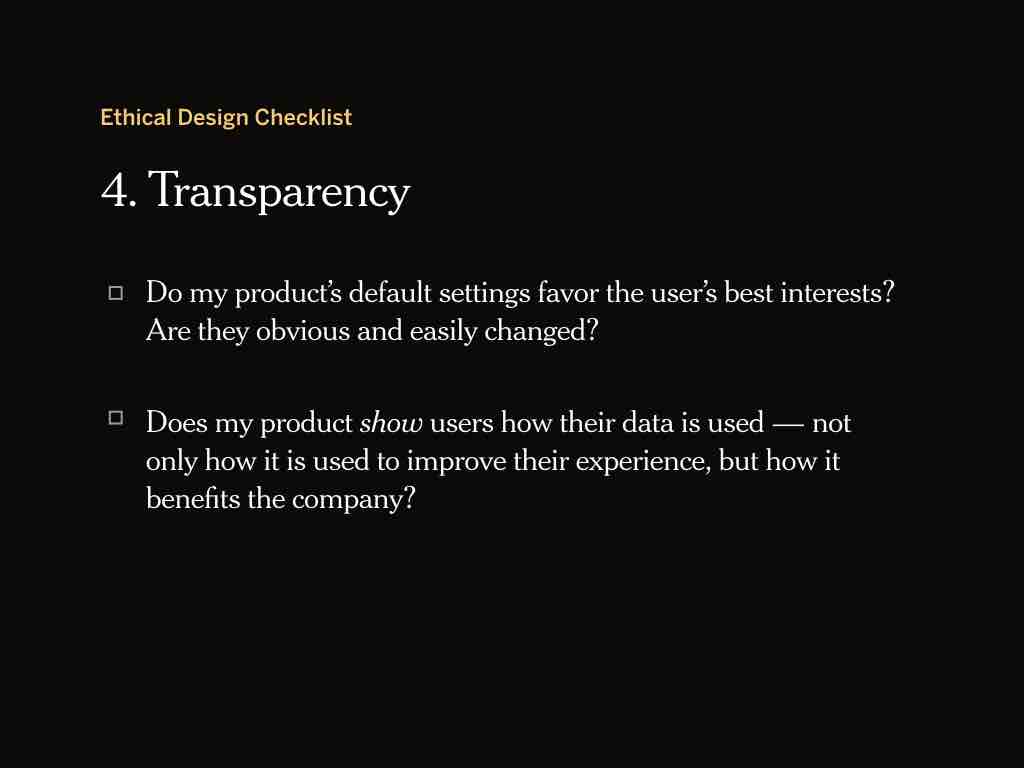

Do my product’s default settings favor the user’s best interests? Are they obvious and easily changed?

Does my product show users how their data is used — not only how it is used to improve their experience, but how it benefits the company? Have I taken steps to reveal the workings of my product in easily understood ways, using “ beautiful seams” rather than creating an opaque product for the sake of simplicity?

Have I anticipated the harm that could be done with what I have designed, and am I willing to accept the damages done by bad actors? Have I communicated these risks with my client? "Your job is not just to produce that work but to evaluate the impact of that work. Your job is to relay the impact of that work to your client or employer” (Monteiro, again).

Have I established a process for assessing the results of my product: not only how it impacts the business, but how it impacts its users? How will necessary changes be made?

Will my product make the design industry more trustworthy, credible, and reputable in the eyes of my users and clients? Am I creating a better future for the next generation of designers? If all designers made decisions like mine, would our industry be in a better state?

I encourage you to think about these questions, maybe write some for yourself or for your team. Here's a link to a PDF of them: Toward an Ethical Design Checklist

I’d like to close with a story. About seven years ago I was working in Chicago at an ad agency, and contemplating my first career change.

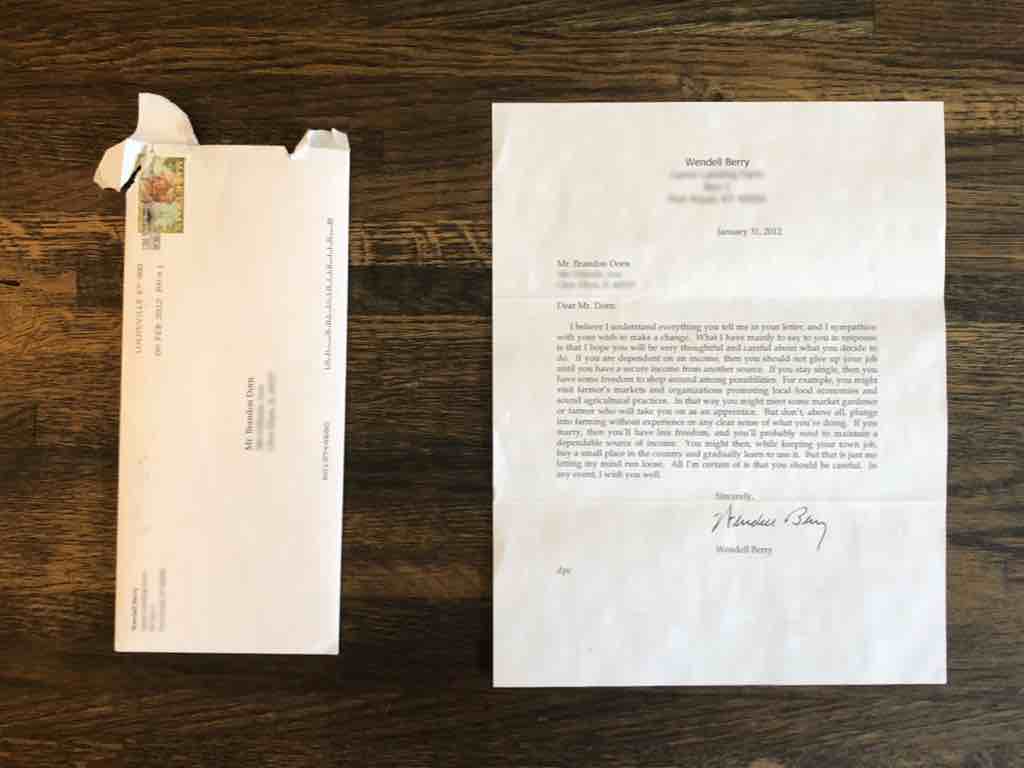

At the time I was reading books by Wendell Berry, a name some of you may recognize. He’s an author and farmer in Kentucky, and has very good things to say about technology, and agribusiness, and small-scale community life. His essays shaped the way I view the world, and still do. But at the time, I read him quite literally, and was intent on leaving the city to join my wife in rural Illinois and become an organic farmer.

Now, I didn’t grow up on a farm. The closest I got to farming was pulling weeds. So although I was set on leaving my job and the city, I was hesitant about jumping in. One day I wrote Wendell a letter to ask for his advice. To my surprise, he responded.

In measured words, he talked about how I might first learn skills from other farmers, and maybe save up to buy some land. Then he gently, but firmly gave me this advice: “Don’t, above all, plunge into farming without experience or clear sense of what you’re doing.”

Sobering words, but they were what I needed to hear. He helped me understand the challenge of what I’d be getting into if I wanted to become a farmer: it would be strenuous, and I would do more damage than good — to myself and others — if I went about it without the right care, perspective, and experience. It would be complicated.

I think about that letter often, even in my decidedly non-farming career. It’s striking to me that no one really gives us this kind of advice when we begin working in technology: we aren’t told to approach it with care, or about the challenges and risks of what we’re taking on. We aren’t encouraged to develop a “clear sense of what we’re doing,” individually and as an industry. Up to this point, we’ve mostly been told to innovate, to increase conversions, to disrupt. We’re slowly realizing that the values of Silicon Valley are not sustainable. We need to find other ways of doing technology.

In one of my favorite essays by Wendell Berry, “Think Little,” he considers how we might come to remedy the damages we’ve done to the earth by living our modern lives. It’s the biggest problem in the world. And you know what he says? Start a garden. “I can think of no better form of personal involvement in the cure of the environment than that of gardening.” It teaches us our dependence on the earth. It is a source of uncontaminated food. It reduces the trash problem. It is a way to serve others. “If we apply our minds directly and competently to the needs of the earth, then we will have begun to make fundamental and necessary changes in our minds.”

The way we act influences the way we think.

I believe that a better web starts small. We need to figure out how to do things right, in our workplaces, with our clients, on our smaller projects, if things are ever going to change on a big scale. This isn’t to say that us folks in small-tech should care about different things than those in big tech, but that the ethical problems in big tech are so entrenched, that it isn’t at all clear to me how they’ll actually change, short of massive regulation. The seeds of change will start on a small scale.

I like what Aral Balkan has to say about this. He is an outspoken critic of what he calls “surveillance capitalism,” basically, the way companies like Facebook and Google gather and sell information about users. The services seem free, when in reality WE are the product.

He does this interview where he’s asked how small-scale alternatives to big tech platforms will scale. Like Duck Duck Go, a search engine that doesn’t sell user data. He says this:

“How will these alternative scale? The answer is they won’t. Our success criteria are not their success criteria. The only thing that will scale like Facebook is another Facebook. We don’t want to build another Facebook. We’re talking about the difference between factory farming and organic farming. We’re trying to build a sustainable system, a sustainable world. It’s not about technology.”

Something is wrong with the way we define success in the digital world. The things our industry aspires to.

A sustainable system. This is what we should be after. Because I believe that, as an industry, we’re working on borrowed time. The current way of doing business isn’t sustainable, and the public is questioning the benevolence of digital technology and technologists.

Building a sustainable system requires us to rethink design. It requires designers to have a moral imagination that goes beyond usability, beyond accessibility, certainly beyond the screens we’re designing.

We as designers and developers can do this. Each and every one of us has the power to create ethical technology inscribed with human values. This won’t come from the top. It will start small.

Thanks for listening.